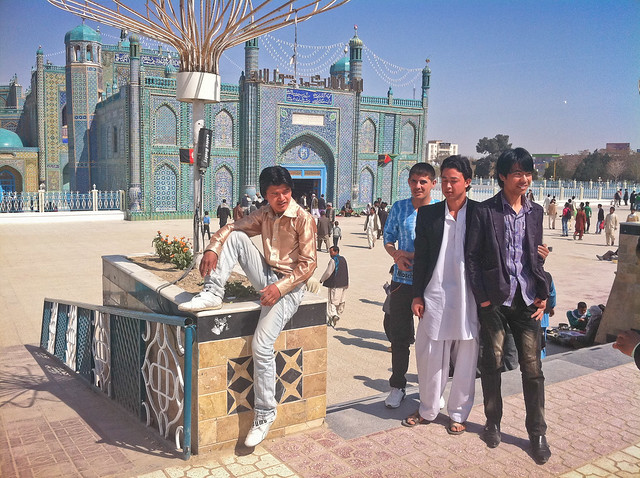

Celebrating Nowruz in Mazar-i-Sharif

We chose to celebrate the Persian New Year, Nowruz in Mazar-i-Sharif because it is the epicenter of celebration in Afghanistan. Over 200,000 people congregate at the Rowze-e-Sharif Mosque which the Afghan Shia believe houses the tomb of Hazrat Ali ibn Abi Talib whom they consider Islam’s first Imam. Nowruz is officially recognized as a national holiday and high ranking officials attend the celebrations.

Although the festivities are centered on the Mosque, Novruz is a pre-Islamic holiday that is not mentioned in the Koran. Because of this, according to some of the Sunni tradition, it is considered bid’ah (a prohibited addition to the religion.) The Shia on the other hand, consider it a celebration of Hazrat Ali’s ascent to the Caliphate on this day in 656 AD.

Both the concentration of people and the religious tensions surrounding the holiday gave us good reason to stay especially alert. The Afghan National Army (ANA) was equally concerned, essentially applying a thick security blanket to the center of Mazar, prohibiting any civilian car traffic and screening pedestrians.

Airport

Civilian Airports in Afghanistan aren’t much more than an airstrip surrounded by barbed wire. You land, walk onto the tarmac, out the chain link fence and you’re done.

At 8AM on the morning of Nowruz, we found ourselves in a desert, 8 miles outside the city, carrying a heavy load, and without transportation. Because of the military lock-down, transport vehicles were not able to reach the airport.

For at least a mile on the road leading to the airport, ANA soldiers were spaced every fifty feet. They shifted their weight from foot to foot, smoked cigarettes and stared out across a vast flat plane.

There wasn’t much for us to do other than walk, and so we did.

A convoy blazed past us towards the airport. It was comprised of fifty fancy SUVs, (Mercedes, Audi, and Toyota Landcruisers) followed by fifty police and military trucks, mostly 4x4 Toyota HiLux pickups (a favorite of the Taliban) with four seats in the truck beds for soldiers with guns. Many had machine guns mounted on the roof of the cab.

Coincidentally we landed at the same time as President Hamid Karzai and Governor Atta Muhammad Nur and these boys were here to escort them into town for a public appearance at the mosque.

After a few miles of walking, we found a taxi which we shared with a fellow pedestrian, a UNDP employee. As the city was cordoned off, the taxi dropped us on the perimeter.

Hotel Barat

Hotel bookings were at a premium for the duration of Nowruz, hard to find and with gouging prices. We relied on our friend Maiwand (the captain of Mazar’s basketball team) to secure us a room at a premium location. But in order to honor our reservation, the hotel insisted that we pay for several extra nights in advance. As this was the best option (and frankly there wasn’t another) we had to give in.

Working through a maze of security checkpoints, we eventually got to our hotel. On the way we learned that the mosque grounds were only open to women in the morning (at least until after Karzai’s appearance.)

Reception struggled to find us a room, saying that they assumed we weren’t coming since we hadn’t showed up two days ago. They had to concede all sleeping spaces to the soldiers who were everywhere, even on the roof of the hotel, and had cots there too!

We responded that we paid for the two nights before our arrival only because it was their condition for reserving the room. Eventually, they kicked out the soldiers and gave us a room on the top floor.

From our window, you could survey the entire grounds and gardens of the mosque. They constitute a sizable city park, a square perhaps a quarter mile to a side.

It was a display of primary colors. The blue tiled mosque was gleaming in the center. The gardens were festively decorated with garlands and streamers, but predominantly verdant green.

Thousands of white doves provided an areal blanket, while helicopters made surveillance laps above them, dropping confetti and toys on little red parachutes.

All the TVs were streaming live from the main courtyard of the mosque. Karzai was about to speak. We were so close that we heard the loudspeakers first and then the TV screen with a slight delay.

Given that we missed a night of sleep, Lou and I actually tried to get some rest. An hour later we were jarred awake by the sounds of artillery fire. Along with other hotel patrons, we ran up to the roof to investigate. When you hear gun fire and music in Afghanistan, you’re taught to interpret that as a wedding party. This is also the reason why many wedding parties had been bombed until the military learned to review their intelligence better.

It turned out to be a celebratory salute to Karzai.

The Funfaire at the Blue Mosque

Failing at sleep, we explored the center of Mazar, its fresh juice stands and shawarma joints. When the restriction on males was lifted, we entered the grounds of the mosque.

The atmoshpere resembled a carnival with vendors of colorful balloons and toys, blanket spreads of semiprecious rocks, jewelry, festive decorations, henna, surma, women’s panties and silk robes.

(Night also revealed thoughtfully illuminated sculptures and billboards arrayed with LEDs.)

Everyone, but especially the youth, were festooned to the Nowruz max. Girls and boys were actively participating in the gaze economy, the cautious give and take, yet not too much of either; casting furtive glances, and if caught, walking straight away.

The boys put on their shiniest shirts and fanciest brimmed hats.

I even saw some girls faces, something entirely unimaginable in Jalalabad. But even under the blue burqa clad majority you could spy the glamor of the outfits beneath and guess at the deliberation expended to compose them. Little accents on their ankles and toes communicated volumes with the small canvas that modesty afforded.

Were you a bachelor in this climate and only focused on the candidates whose face you could see, you’d be discriminating against the majority of the population. I must admit, there is a certain intrigue in not knowing what is behind the curtain. We saw a boy, tailing two glamorous girls in burqas, tempting them in a very universal way, “I have a car.â€

This gave new meaning to the term “blind dateâ€.

It all felt very foreign from the Afghanistan I came to know and rely on while living in conservative Jalalabad. While even in Jalalabad it was impossible not to read into the personal frustrations of everyone you got to know individually, it was never on public display, like this, by everyone.

They say that one of the miracles of the mosque is that when a non-white pigeon appears, it soon turns white. Though I have no proof, I think that what actually happens when a non-white one appears is that the caretaker kills it, or maybe tries to give it a whitening bath in bleach with the same result.

Jahenda Bala

In the inner courtyard, a group of Shia huddled close and were working themselves into a trance by chanting. They were present for the Jahenda Bala, a flag raising ceremony, commemorating the colors of the banner that Hazrat Ali raised in battle for Islam.

This religious practice was prohibited during the time of the Taliban and to the conditioned eye of a Sunni Pashtun, it still seemed like the work of heretics.

Even Najib revealed his prejudice. His face became flush and he said, “Let’s go. I’ll tell you about this later.â€

Afghan National Army’s most heavily armed man

We spent a couple hours waiting for Najib’s friend Sheikh in the company of the ANA’s most heavily armed man. He had a quiver with four RPGs and carried another loaded one in his hand.

Najib guided us next to him and remarked that we were in the safest place in town, but I did not agree with his assessment. There wasn’t a place for miles in overcrowded Mazar where such a weapon could be used effectively without substantial collateral damage. In fact, being next to such a war machine made me feel like more of a target.

Besides, the RPG slinger said he had only ever fired four rounds, all for practice. It’s an expensive pleasure. He claimed each round cost $10,000 but I doubt he knew what he was talking about.

There were a few kids hanging out with the soldiers. Frequently, they’d ask to play with the guns or just tugged at the barrels without asking. And soldiers, who were Afghan kids themselves and could relate, obliged, nonchalantly passing the guns around without so much as a word of caution to not point them at people.

Sheikh and Nasir

We were waiting for “Sheikhâ€. He’s a business associate of Najib’s relative Nasir. Nasir had recently run up a huge debt with Najib and then disappeared. Such a thing strains but doesn’t nullify friendships. Najib lamented, “if only we were still on good terms with Nasir, we could ride across the entire north of Afghanistan and have people slaughter goats in our honor and show us a good time. Sheikh was our stand in for Nasir and though I don’t know what it would have been like with Nasir, Sheikh was an excellent host.

Sheikh carried himself with the air of a successful businessman on the verge of securing a large construction contract with the Americans which would make him even more successful.

His first gesture was to give a crisp 100$ bill to his nephew (who doubled as his minion and driver) to get us “somethingâ€. He then flagged down a Pashtun police commander and got us an escort to the governor’s privately owned amusement park on the southern reaches of the city.

Once inside, we were surrounded by blinky lights, LEDs, glowy orbs and illuminated sculptures. It was strangely reminiscent of Burning Man. Frankly, much of this adventure felt that way. Najib got ride tokens.

Ali

In line for one of the carousel rides, we met a Russian speaking boy, Ali. He overheard me talking to Najib and came to make friends. We talked about his time in Russia, his fascination with Hip Hop. On his shoulder he carried a large boom box. He wore huge sunglasses. His skater hat was at an angle. His shoe laces were neon green and pink. We were yelling in Russian, English and Pashto, all of Sheikh, Ali, Lou, Najib and me; all screaming over each other, merry making. One of the guards approached us and tried to get Lou to leave the men’s line (where we all were and hadn’t even realized there was a separate one.) Najib and Ali started berating him loudly, eventually shooing him away. We were whipped around on tethered swings and even got pudgy Sheikh to strap in for the flight with us.

Other People’s Women

We toured the amusements and spotted a large group of girls sitting around a picnic blanket. Najib cautioned us about walking too close. He said that they are other people’s women and if we approached too close, we may have to resolve the matter with their men.

Chars

Sheikh’s driver reappeared with “chars†(the Afghan word for hash). Sheikh’s chars handling skills were masterfull, like a true charsi (chars user). We sat on train tracks in the process. Through Najib’s translation Sheikh inquired about the logistics of coming to the US and specifically how much money he’d need to save up in order to have a week’s worth of good times. “Will $20,000 be enough?†I asked his intentions. He replied defensively, “no casino, no bars, no girls… just normal things.†I said that a few thousand should be plenty. “And what if … what if, we did some casino, some bar and some girls?â€

Jama Khan

The next day Sheik showed up with a new side kick, 19 year old Jama Khan. Jama is the son of warlord Comandan Haji Akhtar دمØÙ… رتخا ÛØ¬Ø§Ø Comandan Haji Akhtar is on the Balkh Provincial Council and has a pretty awesome ride (4x4 SUV).

According to Jama and Sheikh, Jama’s oldest brother Wali Muhammad Ibrahim Khil was killed by Americans after the governor Atta Muhammad Nur told them he was working with the Taliban. Whether he was or wasn’t, it used to be that saying something like this to the Americans was a rather good way to eliminate a powerful competitor.

Sheikh was tentative with our plans. “Where you want to go? How about you come to my village?â€

Ah, that elusive Afghan village(!), idyllic, pastoral, wonderful, and … everything, except it’s infested by Taliban.  (Najib tells us that this is especially true of Sheikh’s village.)

Sheikh insisted, “I’ll make sure you are safe.â€

Najib said “Thank you, but NO†on our behalf and instead we aimed the SUV for the neighboring city of Balkh.

Picnic in Balkh

Balkh is a frail older brother to Mazar. It is an ancient city (4,000 years old) and a historical center of Zoroastrianism. Due to a Malaria outbreak in the late 19th century, the regional capital shifted to Mazar-i-Sharif (but the province is still called Balkh.)

In contrast to Mazar’s square grid around the Blue Mosque, Balk is arranged in a radial grid around a circular park containing the Green Mosque.

While his minion picked up a bag full of meat in town, Sheikh gave us a guided tour of the park. We then dropped the meat at a nearby relative’s house which we simultaneously raided for picnic supplies: a large thermos of tea, a whole service of tea cups, vinyl table cloths and woven rugs.

From there we climbed the ancient city walls of Balkh to get good views and to select the perfect (read “isolatedâ€) picnic spot. Sheikh decided on a furrowed field next to a shady grove where he unfurled the carpets in such a way that the furrows became recessed rows of seats around an elevated table.

A few more relatives appeared with the meat, already prepared, in a pot.

Hungry, we ate the lamb, the Afghans teaching us to suck out the marrow, and got our hands greasy and then handled cups of tea and Pepsi bottles, spreading the grease; and then made futile attempts to wipe our hands clean with tissue papers, which are the napkins of choice in Afghanistan.

What if “men with guns†appear?

The conversation turned to the subject of safety and how nice it is that we are sitting here with a warlords son (Jama Khan) which would be useful if men with guns appeared.

To which, Jama responded by saying that we’re safe not because of him, but because Sheikh is here.

To which Sheikh said, that if guns appear there won’t be a Sheikh here, because guns are guns and bullets don’t discriminate.

To which, everybody laughed and considered the situation resolved to the extent possible.

Kids’ Table

Not twenty feet off, behind the grove of trees, a few kids were picking at the mud and glancing at us with mischievous faces. Sheikh first shooed them away, but when they didn’t budge, he invited them to eat with us, and when they proved too shy to respond, he rounded up a bunch of meat on a plate and half of a Pepsi bottle and gave it to them. And so our picnic picked up a children’s table.

Girls can drive?

Back in Mazar, Sheikh itched to go back to the carousels. Jama Khan wanted to drive his jeep into the mountains. We compromised by driving out of the city past the carnival grounds where Jama could show us a bit of reckless driving. Then he turned to Lou and said, that if he could see a girl drive a Jeep offroad that would really make his day. And Lou took him up. In all our time in Afghanistan, we saw a female the behind the wheel just once, (and it was the Shari-Naw neighborhood of Kabul.)

Ransom for a Good Time

We initially met up with Sheikh in order to pay him back the 100$ deposit he had submitted on our behalf to Hotel Barat. And while I had given the moneys to Najib, he hadn’t completed the transfer to Sheikh. When I asked him about it, he said “Wait, I’ll give it to him at the end. This way he still has a reason to hang out with us and show us a good time!â€

Our final day in Mazar we got some shopping done, and before long Jama Khan was calling asking to hang out. He showed up with a body guard who he proudly announced was on the ministry of interior’s payroll. To prove the point he made the boy pull out his ID card and show us. Surprisingly the ID card was also his salary card. It doesn’t really matter who you are until you show up in front of the cashier at the bank. When you collect YOUR salary is when it is important to know who YOU are.

Today Jama wanted to go show us the mountains he didn’t get to the day before, and so we drove south, past the gargantuan Soviet bread factory, past the carnival grounds, past empty streets of subdivided lots with retaining walls and some construction, and then streets with lots without construction, just retaining walls, and then lots, but no retaining walls, but just gravelled roads in a grid, and outdoor sewage ditches marking their boundaries anticipating the city’s expansion. There were only shepherds there to graze their sheep, though there wasn’t much (left) to graze. The sheep tried to escape the heat by hiding in sewage ditches.

But Jama drove onward.

Juma Khan drove without regard for streets. He re-landscaped the hills.

All of these plots, I learned later, were from a planned expansion of the city orchestrated by the governor. We’ll be bigger soon! The state can make money selling plots of land!

After driving for a while we seemed no closer to the mountains in the distance. We were in the steppe and occasionally you could spot another group that voyaged to these hills.  This is where they came to escape the bustle of the city (and the Taliban of the village.) This is where they came to be alone with their families. These were the “mountains†that Jama wanted to take us to, as this is where he would come with his friends, rip donuts in his 4x4 and toke the chars.

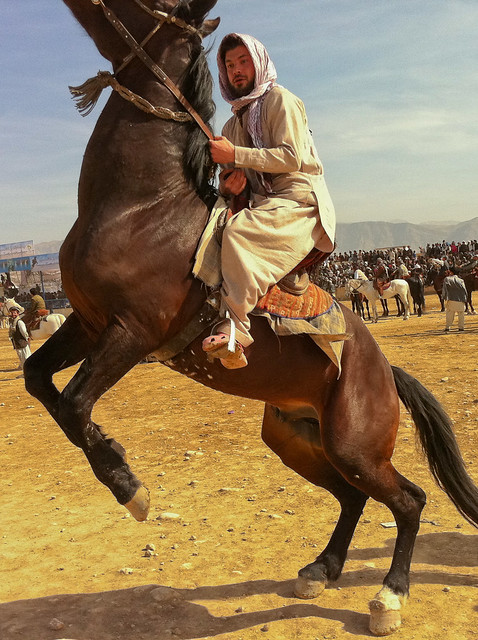

Buzkashi

(Click here for a more in-depth description of the game. )

Novruz is also the culmination of a Buzkashi season and so we asked Jama to takes us to the match. It became clear after some prodding that he didn’t feel comfortable going.

It turns out that just like American oil tycoons buy football teams, Afghan warlords maintain stables of buzkashi horses and teams of star riders under their care.

The buzkashi field therefore is not really a safe place. It’s proxy war. But real war occasionally breaks out in the stands also. It’s the one public event where personal scores are settled by assassination.

In the end, Jama agreed to take us, but “only for a little bitâ€.

These buzkashi grounds were very different from the muddy snowy pit we visited in the Panjshir Valley. It was a large hot dusty field lorded over by a gargantuan Soviet bread factory. On one side were the stands, seating several thousand people. A water truck was zig zagging through the field during the game, spraying the ground, trying to keep the dust down.

Jama disappeared and left us with his body guard. When he returned, it was on a horse. The buzkashi horses aren’t too tall, as then it would be too hard to reach down and grab the dead goat from the saddle, but they are hard workers. All of the horses were drenched in sweat yet they persisted in running full gallop at the minimal urging.

In fact, a buzkashi horse is hard to keep still. If you don’t do anything, it takes off. It’s like having a car without the gas pedal. It always assumes the pedal is floored. You have to actively say stop.

The horses are also remarkably easy to rear. Both Lou and I gave the horses a try and successfully got them on their back legs, kicking in the air, over and over again.

With Jama by our side, we were a part of the action rather than passive observers.

Our schedule was tight. From the horse track, we went to the basketball court.

Basketball Practice

My pipe dream for Mazar was that Najib and I get to join the Mazar basketball team for a practice session. I tried getting in touch with Murtazo, but for a couple days all his text messages reported that his father forbid him to go outside because it was dangerous.

Our connection was Maiwand, the captain, the same guy who helped us out with the hotel. When we met Maiwand, Najib grabbed him lovingly and they walked hand in hand all the way to the basketball court.

Neither Najib nor I were prepared to play, but they took care of us, giving us sneakers and shorts and uniforms and we went through the whole stretching, warmup and exercise routine. They split us up into teams and we played a few practice matches.

At one point, there was a loud BOOM and a pillar of smoke rose just behind the wall of the court. Some of us ducked to the groud, but then Murtazo laughed, “it’s just a truck tire blow out!†and we went back to playing.

Half way through practice, there was a tea break.

Many of the boys spoke to me in Russian on the court. They were commonly Uzbeks or Tajiks educated across the border. The coach had also studied in Russia.

Najib tried some fanciful spin move and ended up twisting his ankle. Just as he sat on the bench, Sheikh arrived. He came bearing gifts, some perfume for me and face cream for Louisa. At that point Najib asked him for Nasir’s whereabouts and gave him the 100$ bill.

Farewell Afghanistan, farewell Najib …

The next morning we were out of Mazar and the next day we were in Delhi.

Naijb was on the verge of tears when we parted. “It will be boring without you. Thank you. You’ve changed my life. I will never forget you.†I owe him at least a blog post, and probably a lot more, so that you will understand why.

I’ll just add, since it’s a feeling that I’d rather not forget, but when we boarded the Air India airplane in Kabul and I saw the female flight attendant walk by in a pair of tight fitting pants, I felt abashedly titillated. There was a sight I had been deprived for the past three and a half months. Absurd, I know, sorry.

Goodbye Jalalabad

The wind picked up on our final morning in Jalalabad. It was soon strong enough that we locked our windows and yet it howled through the cracks. By the early evening the gusts were so strong that they broke windows on the upper deck, broke our deck furniture and knocked over many plants.

We were about to leave Jalalabad, our adopted home, where I spent 1% of my life. Before heading back to San Francisco, we decided to do some in country tourism. The following day was Novruz, the Persian New Year, and we planned to spend it along with 200,000 other pilgrims in the epicenter of the celebration in Mazar-i-Sharif, the capital of the northern Afghan province Balkh which borders Uzbekistan, at the Rowze-e-Sharif Mosque housing the purported Tomb of Hazrat Ali.

Novruz is defined by the Vernal Equinox, which happens when the sun crests across the true celestial equator. Terrestrially we experiencing major shifts as well.

After Lou and I finished packing we huddled together with our coworkers to drink wine and watch the telly (for perhaps the first time.) Bombs were falling in Libiya. Egypt had experienced a coup. Other North African and Middle Eastern countries were undergoing or on the verge of revolutions.

Road to Kabul

I eagerly anticipated a certain photo opportunity on the way out of Jalalabad. Just a few miles west of our compound, near the Darunta dam, I had previously spotted (but failed to photograph) an amusing billboard with a cartoon depiction of a gaggle of bearded Afghan villagers happily handing over a Stinger missile to ISAF forces in exchange for money. No questions were asked. Everyone was smiling.

It was an advertisement for the Stinger buy back program. During the 1980s, the CIA “donated†~2,000 shoulder fired Stinger missiles to Mujaheddin “friendliesâ€. These missiles which could be used to shoot down Soviet helicopters and tanks, had a significant impact in the outcome of the war. The Pakistani intelligence agency ISI had distributed them without much accounting. Consequently, no one knows how many are still floating around. Now the US has budgeted millions to buy back stray missiles for upwards of $100k a piece. It’s cheaper than the consequences. And this creates an interesting economic valuation climate for weapons. How much is your enemy willing to pay you not to shoot at them? The “ransom priceâ€.

On the way out of town, we noticed that many of the billboards had been knocked down by the wind. Just yesterday, they were still covered with election posters six months past their due. I had wondered just when they’d be taken down and by whom. The billboards that hadn’t collapsed entirely stood warped and bare, picked clean by the sand blasts of wind.

The road to Kabul follows the course of the Kabul river, winding its way along the southern bank through hills, past three partially functioning and eternally under-repair dams, and finally up a narrow, dangerous, serpentine gorge locally known as Mohi Par (fish’s tail).

The road is dotted with makeshift shacks selling the available bounty of the land. Today men waved reams of river fish and kids shook bunches of mountain vegetables at oncoming traffic.

We passed a couple fuel tankers, a favorite target for IEDs, Their rusty tanks were leaking fuel right on the road.

Next we encountered an oncoming Afghan National Army supply convoy. Unlike ISAF convoys that drive slow and flock together, ANA seems engaged in a race with each behemoth for itself swerving around the curves.

Remarkably, right before our eyes a large container flew off the back of one of the trucks, bounced on the road, and spilled its booty of ANA uniforms onto the road.

- “Stop,†I yell to our driver Najib. I sense a really epic souvenir pickup. Gotta get this one quick. He skids to a halt, but so does the car behind us. Other people have the same idea. I run towards the uniforms and so does the grey bearded Afghan from the second car.

But before we’re able to snag the uniforms, the next truck in the convoy rounds the corner, stops in the middle of the road. Soldiers hop out with their rifles and stare us down.

“Alright, you win. You can have your uniforms.†I go back to the car with my heart pounding. Damn, it was close.

Face to Face

The motto “every car for itself†applies to every vehicle on the road. They swerve onto oncoming traffic trying to eek out ever more lanes out of two. If it wasn’t so dangerous their optimism would almost be laudable.

The one way I can explain it is that they are making a rational calculation where the variable that is drastically different from my own valuation is the value of one’s own life.

“This didn’t happen during the time of the Taliban,†said Najib. “Everyone knew their lane and what would happen if you veered outside of it.†(Of course, there were also fewer cars.)

Now what you get is a lot of avoidable gridlock. They call it glibly “face to faceâ€. It sounds nice. Sorry we were 5 hours late, “we had some face to face on the road.†And everyone understands that what is meant by this is that cars piled up for miles on a two lane road face to face without any room to maneuver. It takes a lot of coordination to clear such a mess. Eventually, somehow, with guns waiving in the air, we drove out of it.

Kabul

There was one errand left to run in Kabul. Â We needed to purchase a few point to point antennas so we headed to the computer shopping district. Â A man with a riffle walked into the store and pointed it at the shopkeeper. Â After a few seconds it became clear it was a joke. Â Ha, ha, Afghanistan.

We dropped our stuff at Una’s (the newest member of SSF but quite a veteran for an expat in Kabul) and headed out for dinner with a couple of her journalist friends.

One of the journalists, Omar Malick had just completed a documentary in Pakistan and come out to work for Basetrack.org a Knight Foundation Grantee that used Facebook to report on 1/8 Marines deployment in Kandahar. He was now straded since the military chose to terminate this experiment. Omar had instead thrown himself into iPhone hipstamatic photography and shared some amazing shots over Thai food.

Together we roved to a Novruz party at a compound of an Afghan “consulting†firm where the spread resembled that of an American college dorm party. Beers were stacked in a pyramid. Chips, salsa and munchies for appetizer. “Pizza is on the way.â€

The hosts asked us to “not be too loud and disturb the fundamentalist family that lives next door†as “they might do something about it.â€

The attendees were Afghan staff of NGOs, the UN, or various government ministries. Think of it like an Afghan beltway crowd.

The guests and employees alike were mostly educated at liberal arts colleges in the West and unanimously felt like American money was being thrown at them to try to solve the “Afghan problemâ€. Jokes around the camp fire revolved around writing impact reports and USAID proposals for firewood, which was running low.

“Afghanistan is where the money is at. For educated Afghans and for security contractors, that’s the best windfall. Where else can twenty year old boys and girls consult governments [by the seat of their pants, sometimes by just being the eyes that read on behalf of the illiterate]?â€

There was a rumor about the possibility of fireworks for Novruz so we ascended to the roof. After the countdown to midnight, nothing but the scent of Hindu Kush and gentle giggles was heard.

Airport

An early morning “Hope Taxi†gots us to the Airport. Six chambers of security, each with a male and female line, neither more secure that the last, and we’re in the main hall.

We have a Pamir Airways e‑ticket to Mazar-i-Sharif for three people. We’re happy to have Najib along. We’ve become so close and these are our last four days together. Because of the holiday the airport is crowded more than usual.

We check in at the only counter that says Mazar, even though it actually seems like a different airline. Bags are checked, paper tickets issued, no hitch.

Through another tier of security we find ourselves resting in the waiting lounge.

Out of the corner of my eye, I spot the airline employee who checked us in with a look of consternation. He’s clearly looking for somebody. He’s heading straight for us!

Evidently the Pamir fleet was grounded as part of a general Kabul Bank lending practice shake down and the airline’s inability to repay a shady $98 million loan. The airline was shut down two days before our flight. We saw Pamir planes parked at the airport. Ironically, their online ticket sales website is still running, while we are still out $900+ for our flights.

He explains to us that we had purchased tickets for an airline that ceased to exist by the time we got to the airport. He had mistakenly issued us tickets and now insists we actually pay for them to get on the flight.

Naturally we protest, but as absurd as it is, it was also clear that he was speaking the truth. No, he didn’t know how we would go about getting a refund from Pamir, but then again, neither did the many other people who were in the same situation that we were.

We paid and boarded.

To be continued …