Of Lions and Horses in the Panshir

Last Friday morning we headed off at first light from the muddy streets of Kabul. We wound our way north, past Bagram, where ISAF is headquartered, and took a sharp turn east in the village of Jebal Seraj. We’d decided to take a day long pilgrimage, of sorts, to the tomb of Ahmad Shah Masoud. His grave lies deep his homeland of the Panshir Valley which he so famously defended against the long and arduous Soviet attack.

Masoud is arguably Afghanistan’s biggest hero. Throughout Afghanistan his picture is displayed in car windows, posted on buildings, or memorialized in woven blankets. The day he was assassinated, September 9, 2001, by suspected Al Qaeda agents posing as journalists, is a national holiday. He earned his title “The Lion of the Panshir” defending his home turf from the Soviets during the attacks of the 1980s. Lions are intrinsically part of Panshir culture. The word itself means “Five Lions†and we saw election posters for a candidate whose symbol was four of the majestic beasts. (Each candidate is “randomly assigned†a visual symbol so illiterate people can recognize their candidate on the ballot. It’s well known that with the right funds and connections it is possible to influence on this “random assignment.†One political party paid for all of its candidates in different races to have apples for icons, to present uniformity to its illiterate supporters.)

During the Soviet invasion of the 1980’s the Lion of the Panshir and his mujahideen fighters would descend from the valley, attack the Soviet supply chains heading across the Salang pass to Kabul, and retreat with their stolen booty. The Soviets tried to dislodge him from the valley in ten separate offensive attacks. All of them failed.

When the communists fell from power Masoud served in the mujahideen government as Minister of Defense for the few years before the Taliban took power. He then retreated back to his valley, from where he continued fighting the Taliban, (until the bomb hidden in the disguised journalists’ camera made him a martyr.) When he died he was the leader of the Northern Alliance, or the United Islamic Front-an unprecedented multi-ethnic group of leaders who fought against the Taliban government and, once the US began carpet bombing post September 11, took control of Afghanistan.

In 2002 Mosoud was post humously nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. (However, the prize can only be awarded to a living person.) He was buried 30 km from the entrance to the valley, near the village that was his home. Originally it was a plain, simple grave on a large promenade overlooking the valley, but recently a massive marble structure has been erected over the grave, with plans already in construction to add a large mosque and building complex to the site.

This was our initial destination as we made our way up the valley, driving alongside the Panshir river, stopping to climb around in the rusted shells of discarded tanks and helicopters, until we reached the hillside crested with the marble monolith. We paid our respects to the great hero, along side with a steady stream of others, local and visitors, who often stopped to pray at the holy grave site.

The path approaching the site was lined with a variety of Soviet armored vehicles, some spray painted with the Taliban’s symbol (were they captured as Panshiri loot during a battle 15 years ago?). A few bees had taken up residence behind the screen of one of the instrument panels, creating a cluster of perfectly geometrical cells, whose inhabitants and makers were now frozen to death by the chilly winter. Beyond the high promenade, fields spread out across the valley, sewn with snow.

As we climbed around the rusty metal, the wind whipped falling snow at us priming us for some hot tea, so we went in search of a chaihana. As we drove up the valley we stopped to ask men wrapped in green Uzbek robes, huddled against the cold, where we might be able to get some chai and a bite to eat. “Fifteen minutes up the road†seemed to be the standard response. After a few incarnations of this, the road finally passed through a tiny town center, complete with a mosque, a few stores, and exactly one place to get food.

We stomped in and huddled near the fire they lit for us. After realizing all they had was beef broth and tea, so Najib took charge and sent the employees to the bazar for supplies and then ended up cooking up the meal himself. I’ve encountered few restaurants where you bring your own food and cook for yourself.

Grateful to be out of the car and out of the cold, we relaxed on the raised wooden platform covered in carpets. The other patron across the way started chatting with us. We learned from him that every Friday in winter the village played Buzkashi on a field just down the street. They were now on a break for prayer, but would resume the game in an hour. He invited us to come watch.

Buzkashi is the national sport of Afghanistan. It’s a winter sport, played on horses, somewhat like polo. Two teams compete to grab a dead goat and transport it across a field into one of two goal circles. Usually two villages compete against one another and there are cash prizes for the players who score goals.

The match we saw was played in a large field of mud and snow. A clump of players reared their mounts, smashing and pushing one another in attempts to reach down and scoop the 36 kilo dead goat off the ground. Many of the players wore Soviet tanker hats. When asked how they acquired their headgear they answered “We took them from the Russians we killed.” Four hats per tank, hundreds of tanks, you do the math. As they kicked and whipped and pushed, the horses’ and players’ legs alike were covered in muddy brown slush and the goat was indecipherable from a bag of mud.

And so we spent the afternoon huddled against the cold with the entire population of a small Panshir Village, watching horses and men fight each other to carry a dead goat across the valley.

Epilogue: On our journey home we stopped to watch some kids shoot snowballs across a field using a long slingshot apparatus. When they realized I was videotaping they quickly pushed their ace slingshotter forward, encouraging him to display his talent. They then taught Peretz how to shoot, applauding his efforts. His number two shot earned him much whasta.

How the Taliban hijacked our educational materials…

Our Malik Dave had a wonderful idea. The reasoning went something like this:

Let’s employ the Afghan companies that sprung up to print election posters.

They are currently out of work because the election season is over.

Lest we hire them, they may be up to no good.

We call this technique weaponized shopping and it’s one of the techniques in the arsenal of the Synergy Strike Force.

Over the past month, Lou, Juan and crew have put themselves towards selecting and optimizing high quality image files for large format printing of educational materials. We did a test run with the printers and then submitted our final order. Yesterday, (Sunday 20th) Hameed and Najib went to pick up the posters.

As things turn out here, the shop owner had been arrested by the police on suspicion of printing materials for (Al Qaeda or) the Taliban. When the police raided the store, they sensibly confiscated all of the printed materials in their possession as evidence. Among this pile currently in procession of the police are posters on the subjects of cell biology, hydrology, and the periodic table of elements.

Hopefully, we’ll get them back. We did pay a good 4,000 Pakistani Rupee equivalent of 45$ Pakistani Rupees, called “Caldari” are the de facto currency of Jalalabad deposit.

Such a day’s course of events is starting to seem perversely normal for us, as much as I can still imagine seems perversely abnormal for those whom I usually count as peers.

***

Two days ago (Saturday Saturday is the first day of the work week. 19th) an attack took place in the center of town focused on Kabul bank where police officers were collecting their pay. From our sources at the hospital upwards of 40 people have died and many others are in critical condition. Among the dead are reported the “deputy police chief and the head of criminal investigation.”

Many of our friends at the public hospital were on high alert dealing with the patients that stretched their capacity. Meanwhile our friends at a local radio station were broadcasting the need for blood donors across the airways, resulting in hundreds of donors showing up at the hospital, ready to give.

Our friends say that the only day in recent memory that compares at the level of impact was when protests erupted in 2005 after it was alleged that the Koran had been flushed down the toilet in Guantanamo. Â The differences are stark. There are many more civilian casualties and this was not a popular uprising.

***

Yesterday (Sunday 20th) was a day of mourning. Two of our guards had lost a brother. Many of our friends had checked out for the day to attend funerals for friends, relatives and acquaintances. Our UPS (uninterrupted power supply system) had died but we couldn’t get it repaired because the shop of the company that had built it was also damaged in the explosion.

***

We got hold of some exclusive footage.

In this video you see a captured insurgent and security video showing how he entered the bank dressed as a police officer and started firing. Several things stand out. Firstly, he looks like a clean cut young man, nothing like what we have learned to think of as insurgent or terrorist. Second, while he is firing hordes of people run past him, within a foot in distance, and none of them give his vulnerable backside a good whack.

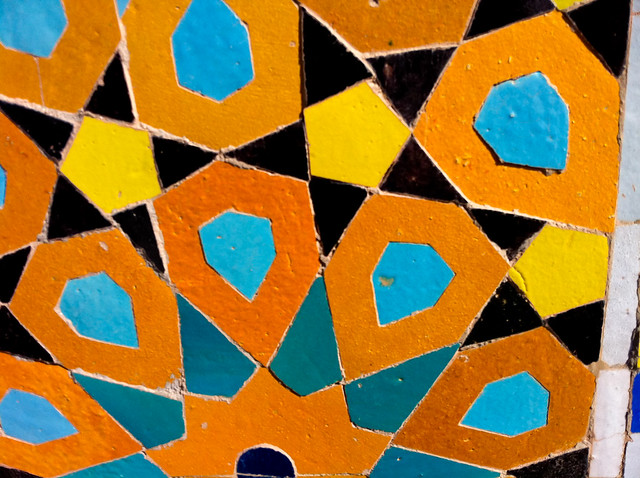

Tile Porn

Presented here for your visual entertainment and aesthetic enlightenment are images from Herat’s Friday Mosque, one of the gems of Islamic Architecture.

Teleconferencing Medicine

Tuesday was one of my most rewarding days in Afghanistan. Â I witnessed something undeniably and irreversibly positive.

In the morning an ambulance came to pick Dr. Pete and me up from the Taj. Â We crammed along with the driver in front, while 5 female OBGYN doctors and a male ward director sat in the back, occupying one bench and the patient cot. Â I’ve ridden in the back of this ambulance before and know that the cot slides around and the whole setup can’t really accommodate more than 3 comfortably. But the back also contained a bunch of endoscopy equipment, which I had taken out of the hospital (where it had previously sat for 7 years unused, after USAID proudly donated it but forgot to teach anyone how to use it, or even bother to figure out whether sensitive expensive equipment from America can be plugged into the unpredictable current coming out of their wall sockets.)

Then again, I have also ridden on the lap of an older bearded Afghan stranger in a Toyota Corolla station wagon taxi where we were 11 all together and 3 women sat in the trunk. Hameed, who was my companion on this adventure, tried to pass me off for an Uzbek who didn’t know the local language. That cover lasted for about 3 seconds until one of the geezers started talking to me in Uzbek, and then laughed that I didn’t know my own language. Then Hameed claimed I was mute, for lack of anything else to say. That excuse lasted for as long as I didn’t speak (3 seconds) since he had failed to warn me of his intentions. They all laughed and the guy told me ‘kine kana’ for sit dude and guided me onto his lap.

Ambulances are not used in the same way in Afghanistan. Â They may sometimes transport a patient from a rural clinic to the main hospital, but mostly they are for off-label uses. The driver is crazy even by Afghan standards. Usually he blares his siren, verves in traffic, as if he were born to be a race cum bumper car driver, playing perpetual chicken on the drag. Today he managed to keep himself mostly in check, probably because of the female doctors.

Today, we were heading to the ILC (the Internet Learning Center) at Nangahar University for the first ever teleconference between the doctors of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and I was a little bit anxious.

Culturally, we men are not allowed to speak to the female doctors (or females in general, other than the ones we brought along with us). Â We cannot look them in the eyes. Â We follow this protocol because we have been told that doing otherwise would make them feel uncomfortable. Instead, our conversation flows through a respected Afghan intermediary. That was the role of the male doctor who is their ward director.

But, you see, sometimes, and in our situation in particular, it is useful to talk, such as, when you need to assess their needs for a particular type of training. Â Do they speak English? Â How well? Â Would an English speaking specialist suffice? Â Should the trainer speak Pashto? Â Is translation only necessary for the finer points?

We got off to a bad start. We were having internet quality of service problems. The conference quality was jittery to the point of annoying. We finally hacked together a solution, using the video feed from the polycom teleconferencing unit while routing the audio through Skype. At last it was working.

Teleconferencing is a visual medium. When we first fired up the equipment and their faces popped up on the screen, I saw the doctors play out their instinct to bring their veil to their faces and hide from public view. We disabled the window-inside-the-window on the projected screen that showed us what the doctors in Pakistan were seeing.  You can hide behind the voice, but not behind a camera; but you can think that you are hidden when the camera isn’t revealing what it sees.

When selecting a location for the conference, we considered several places with passable internet. Â In the past a conference had been scheduled at the Taj, but the women did not show up because of cultural issues stemming from the fact that it is known as a Westerner enclave. So now we were on neutral turf at Nangahar University, (having transported them 10 miles to an internet center that was built by the Rotary Club and to internet that was provided by NATO.)

The female doctors sat in the front row and the men sat behind them.

Dr. Pete’s main gig is running a company that sets up telemedicine capabilities in various hospitals and field clinics around the world. Â Though his working relationship with Holy Family Hospital in Pakistan, Pete got a female OBGYN doctor ultrasound specialist and a female Pashto translator to teach a class on the proper use of an ultrasound.

I was playing general internet and audiovisual tech in the equation.

It started out as a boring lecture. The lecturer spoke, the slides advanced. For me the material was new and therefore interesting. I also had the second occupation of observing the entirety of what was going on. But the intended audience sat silent and seemed bored.

Were female doctors reluctant to ask questions? If so, why? Were they shy? Was it old hat and boring? Were we the condescending foreigners that assumed they were merely playing doctor until they met us and wanted to teach them a thing or two?

Pete was doing a good job breaking the ice, asking “dumb questions”, and managing the flow.

And then, about an hour into the lecture, a new voice piped up. She spoke quietly and was further away from the microphone so it was harder to hear. I climbed around a maze of wires (from the polycom, the projector, the speaker system, the laptop and attached microphone) and brought the microphone nearer. The female doctors laughed at my parkour moves to maneuver the laptop and not snag any wires. We were beginning to win them over.

They asked two or three questions in all. We ran around behind the scenes, printing new handouts that the Pakistani doctors sent over in response to the questions.

Two hours after it started, the class was over. By way of effective classes, this was a failure. Â Very little new information was transfered per unit time.

I positioned myself at the back of the classroom next to the male ward director who has been typing away smartly at this laptop and chatting on his cellphone during the lecture. Â He had a long white beard, designer glasses, and a traditional white cap. I told him that we understand that the class wasn’t perfect, but that we considered this a first test. We would also like to become better and improve the classes and to do this we needed open criticism from the doctors themselves. He walked to the front of the room and translated what I said to the doctors.

And then something unexpected happened. Â They turned and started to speak to us directly. Â Or, under these circumstances, I can be forgiven for erring on the side of calling it directly. Â They expressed their needs. Â They expressed satisfaction at today’s meeting.

At first their remarks were ventured in the void, not addressed to anyone in particular. But then we (also) started to feel comfortable to engage the individuals, responding to individual comments and weaving a common conversational thread. It was a true dialog. Â We took notes: they wanted large, high resolution actual ultrasound images, case studies, examples of normal and abnormal cases. (They said that they didn’t know what normal was supposed to be!) They wanted to be doctors playing diagnose-this-patient while staring at the same raw image. Â They didn’t need a basic theoretical review. They had the books and studied them. They wanted the doctors in Pakistan to show their images, and they wanted to bring their own troubled cases to discuss.

(Please “Please forgive the poor audio quality and lack of editing, but you can hear the banalities of the moment for yourself.” forgive the poor audio quality and lack of editing, but you can hear the banalities of the moment for yourself.)

The women ranged in age from the 30s to their 50s and in this conversation I saw within them articulate doctors who cared about their patients and wanted to become better stewards of their health, but also I saw (forgive me Allah for saying this) youthful excited chattering girls.

Pete pointed out that doctors from developed countries have a lot to learn from Afghanistan. Â Â Since it takes so long for people to get themselves to a hospital, patients present advanced stage pathologies. Abnormalities are so common that you almost have to redefine normal. He told me that when he spent a day at another ultrasound clinic in Jalalabad, he was blown away at the presentation of unusual in every case. Each would be a case study in America. You just don’t see that kind of stuff as a doctor. More cases in one day than he has seen in all his clinical rotations.

We learned a lot from this session, simple banal things.

We learned not to ask, but to just give. You endlessly wallow in self-censoring cultural sensitivity orbits asking whether you can communicate with the doctors directly, but then again, you can just do it. Don’t ask can we have your emails. Just give a hand out with your own, with the Pakistani doctors emails, the coordinators, etc. Add a note describing what role each person plays and put the ball in their court.

At the end Qahar, a friend with whom we collaborate with on various internet projects, walked into the room. On their way out, the female doctors surrounded him. They told me that he is their computer teacher and their English teacher too. It was clear that they appreciated him.

And that appreciation also cautiously reflected on us. They started to trust us that we actually cared and weren’t there to merely wave an illusory magic wand in the form of high-minded advice and grandiose consultation based on “The way we do it in America …

***

Of course, it is dishonest to end on such a positive note. A couple days later, we went for a second victory. The head doctor of the hospital where the women worked was supposed to have a one on one planning meeting with the chief doctor from Pakistan, to plan future training session for doctors from other departments. It was the third attempt to schedule such a meeting.

The time was set on both sides, the venue prepared, various parties were involved. And then, he didn’t show up.

I was sad and it showed when I talked to our friend at the ILC. And he tried to console my by saying, “We are used to this. We plan, we talk, and then when it comes time, it doesn’t work out. That’s normal.”

It’s a big challenge to stop being used to failure. It’s a big challenge to redefine normal.

Traffic fLaws

Ostensibly, in Afghanistan, traffic drives on the right hand side of the road. However, this rule is leniently applied. In Afghanistan the road is used for driving, and if the left hand side of the road is open, a driver will take it.  Today while cruising down the lane of opposing traffic, we had to edge back into the regular flow to pass a checkpoint. The guard was angry.

“Why were driving on the other side of the street??†He demanded, according to Najib’s translation.

“What did you tell him?†I asked.

“That I had foreign guests in the car! [Referring to us]†Was the answer.

I saw one driver in Kabul even drive up onto the sidewalk. No small commitment because the street is separated from it by a 2 foot deep ditch so he’d have to drive the length of the city block before getting back. Still, the road was full of cars honking but the sidewalk only had pedestrians on it- and they learn quickly to get out of the way.

With all this chaos you’d think that there would be lots of accidents. And you’d be very right. The road from Kabul to Jalalabad winds down gorges for miles before opening up into the plains of Nangarhar. This is where 16,000 British Troops and their families were notoriously slaughtered in their retreat from Kabul in 1842. One lone survivor, Dr. Brydon, made it out of the valley to Jalalabad. As the story goes, the Afghans let him survive so someone could tell the tale. Meanwhile, today the gorge is not dangerous because of IEDs or Afghans shooting from the hills but because of horrible driving. Dr. Baz Mohammad, the director of the Public Hospital told me that in this year already there have been 1400 accidents and 300 deaths on that road. He knows because many of the patients treated at his hospital are victims of those crashes. (The Afghan calendar starts on the Vernal Equinox, and so these figures cover 9 months of accidents, not just 1.)

The main road in the city of Jalalabad has a divider down the middle of it, in a futile attempt to keep traffic on its own side of the road. Often it works, but it’s certainly not uncommon to see a vehicle driving the wrong way on your side of the barrier. They’re committing to driving against traffic, acting on the assumption that traffic flowing against them will all spot them in time to swerve around their oncoming car.

There are no road signs in Jalalabad. Drivers indicate they are passing by honking loudly. No on uses left or right blinkers as turn signals, but it is locally understood that flashing your blinkers means you plan on hurtling straight through an intersection, regardless of oncoming traffic. The only streetlights in the city are found at one particularly busy traffic circle in the middle of town. They aren’t powered. Instead, a cop with a shrill whistle and a stop sign the size of small diner plate stands in front of the lights, waving his sign menacingly while being thoroughly ignored by the cars fighting to get by. Roundabouts are common here, and drivers usually go the same way around them. Not always.

Taking a turn, especially a left-hand one, is not for the overly carious. Cars will not let you turn unless you give them no other option. The only way you’ll be let into the flow of traffic on a busy street is if you get the hood of your corolla nosed in far enough that cars can’t swerve around it. The rule of the road is that you never give up space to anyone if you can’t help it. This includes budging an inch for the army truck with 4 men holding AKs in the back trying to wedge its way into traffic. No exceptions given. When we riding in the Teaching Hospital’s Ambulance (they sent it to the Taj for our ride) its driver turned on the siren in a vain attempt to push faster through traffic. The siren had little effect. It could barely be heard above the honking of horns, not that people would have heeded it if it had been louder.

Parking is also haphazard. There aren’t really parking spots downtown so much as there are gaps between food carts where you can stash your car for a while. The cops, Mehrab told me, don’t give tickets because “no one would pay them.†Instead, they go around with a screwdriver and take the license plate of cars parked “illegally.†(The vast majority of parked cars here would qualify as this in America.) That way, drivers have to go to the police station and pay to get their license plate back. The fee is nominal, but the hassle of having to pick it up is supposed to deter.

Most cars are bought on auction in America (after having been totaled) imported and repaired. You often see plates from CA, MA, TX, and even from Canada.

The oddest accident I’ve almost gotten into involved a van diving in front of us whose wheel popped completely off the vehicle. Maybe the nuts weren’t tightened, otherwise they were rusted completely through because the whole tire with its wheel popped off the axle and flew across the road, into oncoming traffic, smashed into the front of a car going the other way, and ricocheted back into our lane. Najib slammed on the brakes as the tire bounced across the road in front of us. Meanwhile the driver of the van had managed to keep control and pull it over to the side, undamaged if you don’t count the missing tire.  The car that took the brunt of the tire seemed to have a smashed front light, but little other damaged. And we cruised between the two stopped vehicles, heading into town.