Disaster Services

Yesterday Megan and I taught CPR to a group of University Students who have taken it upon themselves to form a Disaster Response team and are trying to amass skills and knowledge that will be of use to them and their communities. One of the boys, Hameed, is part of our informal “geek squad†at the Taj and wrote the previous post on this blog. Of the four he was the only one who spoke fully fluent English. Two could get by in English and the fourth spoke none, although he was fluent in Pashto, Dari, Urdu and Russian. Many Afghans in this area can speak and read (if they are literate)  Pashto, Dari and Urdu. If they are in their forties or fifties, they can get by in Russian. The younger generation tends to know dabbling of English. Pashto is the main spoken language but Dari seeps in from the West, Urdu from the East, and Western Languages trickle in through the occupying armies stationed here.

The class was punctuated by Hameed’s rapid fire translation, side conversations in Pashto, and the boys wrestling matches as they were a little overenthusiastic when practicing the Heimlich maneuver on one another. The best part of the class was the myriad of questions the boys had, indicating both a sincere desire to learn skills applicable to disasters they had witnessed first hand, as well as exposing deep seated cultural difficulties that never arose in my numerous First Aid re-certification classes.

Noorahmad probed about how to clear water from a person’s lungs, the memories of last year’s flooding and earthquake still penetrating.

They asked about the spread of infection and how they were supposed to avoid getting diseases when sweeping a victim’s mouth clean or providing rescue breathing. (The next step of preparation involves each of them assembling a medkit, complete with lots of latex gloves).

Through Hameed’s translation, Najib explained to me that he was from a very rural area where there were no trained medical personal in any kind of proximity. He wanted advice for pregnant women that he could bring back to the village and disperse. According to the UN, Afghanistan has the second highest infant mortality rate in the world, topped only by Seirra Leone. It is the only non-African country in the top twenty-five. Access to information on pregnancy and birthing, let alone trained medical workers, is slim at best. Even where there are medical facilities, misinformation abounds. I was shocked to find out last night that the director of the Neonatal ward at the Public Hospital in Jalalabad has never seen a live birth.

Rahmat raised his hand and said “In our culture we are not supposed to touch women. What should we do if it is a woman who is not breathing?â€Although surprising to my western sensibilities, the question is of utmost importance. Most women in Jalalabad still wear their burqas in public. Although Afghan society is extremely physical, it is so in a fully segregated way. Men and boys are always play wrestling, hugging, and walking with their arms around each other, but the two sexes never touch in public.  Meanwhile, in the privacy of the university’s two-month-old women’s dorm, I chatted with half a dozen teenage college girls play wrestling in their own way- hugging, poking and slapping. Still, one girl there was married and five months pregnant yet her husband lived across campus in a men’s dorm. There was no place they could live together within the orbit of the school.

Even in a life or death situation, where a women would die if she were not given a few breaths of oxygen, there is a hesitation if it is the right thing to do. The question was not uncaring, quite the opposite, but it reflected the extreme chasm between men and women which will take more than an effective counter-insurgency force and an army of predator drones to solve. In the end, if these boys ever have to perform life saving aid they will have to make those decisions for themselves.

My Moment of Heroism

Morning rolled around. After having breakfast with my uncle, I headed towards Jalalabad bus station in Kabul. I sat in the rear seat of a wagon. A man with grubby clothes, long hair, dirt-caked hands, wearing a big baggy vest with swollen pockets, lines etched into his tanned face, creases framed his eyes and his mouth, came aboard and sat next to me. His face was pale and his eyes were frightened, like the eyes of a hunted animal. In my country, we hear of suicide attacks everyday, and the signs that the man had were all of a person about to commit a suicide attack on foreign troops in our country. The road I was traveling on is an important highway which connects two major cities, the capital, Kabul and the frontier province, Jalalabad. Foreign soldiers’ convoys travel on this road frequently.

Thinking all about these premonitions, I thought that the man sitting next to me was suicidal targeting foreign soldiers. His eccentricity and talking to himself doubled my doubt. The man on my right looked scared and pale. We traded a blank look. I was trying to fake a smile, but all I could manage was a feeble upturning of the corners of my mouth. He stared at the suspected man, his eyes switching from him to me.

After driving for thirty minutes, we passed Mahipar Valley. I sat bolt upright racking my brains when I remembered my mother who used to tell me stories when I was at seventh grade. There was a line in one of her favorite stories. She would always repeat it again and again: “champions are not made in the gyms; champions are made from something they have deep inside them.” I was rolling my eyes. I asked the man on my right to roll down the window for me. I made the excuse and started talking to him. When I asked him about the dirty man on my left, we were on the same page (he was doubtful too). I couldn’t dare talk to the suspected man. However, I hesitantly shot my first question followed by another bunch. I would either get a nod or a monosyllabic answer which shot up my doubt.

After a few minutes of vacillating from one idea to another, my eyes were suddenly caught by an approaching oncoming convoy of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) and ANA (Afghan National Army). I looked at the suspected suicide bomber. He was moving from side to side looking at the convoy while keeping one hand on his tummy muttering something with himself. Like when someone is dying, they repeat verses from their holy book. When I saw this, I became a hundred percent sure that the scenario seems to be a suicide attack. My Adam’s apple was bobbing up and down. My lips had gone dry. I licked them and I found my tongue dry too.

When you kill a man, you steal a life. You steal a wife’s right to a husband, and rob his children of a father. If you save a life, I believe in some rewards from God. So, I quickly decided to thwart the immanent attack and save my life along with nine other passengers in that vehicle and many others outside.

First, I took a deep breath, focused all my concentration and energy and then grabbed both hands of the man twisted them and turned them over to hind. I felt so strong at that moment that I attacked a thirty year old man and slumped over on his seat with my itsy bitsy body. I put my knee right up against his back. He was screaming and trying to release himself, but he was held so tightly that he couldn’t even move. Loud Afghan Atan music with strong beats of drum and trumpet blared from the speakers in the car. Since we were in the rear seat, the driver couldn’t hear us, so he kept driving. I was holding him as long as the convoy passed us. Finally, I searched him with my foot pretending that I would release him. After a veneer of releasing, I searched him thoroughly. There was nothing explosive to feel hard or heavy with him. His vest was stuffed with empty mineral water bottles and old shopping bags like someone with a psychiatric problem.

After it turned out that the man was innocent, I was very much embarrassed. I received punches, slaps and shoves, but I neither showed any reaction nor cared about it. After exchanging a few words with him, I got to know that he had mental problems and was psychologically unbalanced. After a few minutes, the man raised his hand to scratch his head. I flinched, because I thought it was another one of those slaps on my face. I was mortified and still felt scared tinged with a little feeling of courage and bravery, but I took myself as if I had done nothing wrong.

My embarrassment turned me a little to the right, so that the man couldn’t see me eye to eye. I faced to the passenger on my other side. I saw a smile on his face for the first time since the beginning of the trip. When I talked to him, he thought that he would die with his baby-girl on that day. We rolled up to Jalalabad city. I was about to get off the bus; the passenger on my right addressed me with the nickname “denar bachayâ€, and patted me on my back. He wished me a bright future. I apologized to the suspected man for my mistake and asked him if he wanted to stay with me for lunch. He accepted my apology and declined the invitation. I got back home safe with a feeling of valor. That is how my trip to Kabul ended.

A Small Adventure

(Note: This is the first post by Hameed. Get used to it!)

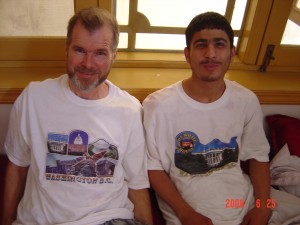

I have an American friend named Jeremy. He is my Pashto language student as well. Our friendship is very tight, and it goes beyond the teaching. One day, Jeremy asked me to travel to Kabul with him because of security problems and to help with translation on the way from Jalalabad to Kabul. I agreed to his suggestion.

It was a bright Thursday morning of humid summer, promising heat, in July 2008. Everything was all set. We took a taxi, and rolled towards Kabul. The trip was very fun. We chitchatted on the way talking about one topic after another. The time passed very quickly. It flew, actually. We arrived in Karte-e-Char at 01:00 pm. Tom- the host wasn’t at home that time. The watchman of his home was a friendly slightly overweight man. Not only did he let us go in, but he helped us to carry the bags, too. We had the key to Tom’s room by having called him in advance.

We sat in the room waiting for the host to come. We had one taco each at the top of Mahipar Valley which hit the spot for an hour. I was very hungry and out of patience, so I asked Jeremy to call Tom if he could come so that we would have lunch together. So he did. Tom said that he couldn’t make it until 8:30 at night. My partner asked me if I could wait until 3:30pm for lunch. I was starving, but my culture didn’t let me say no, so I said, “That’s Ok, no biggie.†Finally, it was 03:30pm and I thought it was time for lunch beyond the shadow of a doubt, when I heard my partner said “Hameed, can you wait for three more hours, so that we would have a big dinner at Rose?” Suit yourself, I replied under breath. ‘What?’ he asked. As…um… as you wish, I said. Jeremy was a man who meant every word he said, but I couldn’t get over how different he was that day. I missed lunch, and I had to wait for three more hours to eat dinner. I was very shy and clumsy. I didn’t even have the guts to tell him that I was starving. I waited for three hours thinking about the American culture, Jeremy, and how he could survive with one taco for twelve hours. I would yawn and steal looks at my wrist-watch three consecutive hours. I felt like a fish out of water.

Eventually, it was seven in the evening. My abdomen began to give low-battery warning by making funny sounds. Jeremy probably heard it. Then he had to take me out to chow down. We entered this western style restaurant, Rose and had a big meal there. We returned home around 8:30pm. Tom had still not come home. He didn’t come until 9:30. He was a very chummy young man and had a bubbly personality. He brewed us some tea right after he came to sound very Afghan and good host. We hung out deep into the night.

Morning came. Andrew, a friendly man in the neighborhood, invited us for breakfast. After the breakfast, I said goodbye to them. Then, I went to visit an aunt of mine in Kabul. Next, as the day was ending and it was getting darker and darker, I stayed at my uncle, Qasim’s home for the night. My uncle and his two children had just gotten their visas to America. Uncle Qasim was extremely happy and he was telling me about their planned immigration to the U.S.

Introducing Hameed!

We kick off the New Year with a new author on our site. Meet Hameed Tasal.

Here Hameed is aligning the Satellite receiver dish atop the Taj. See the earphones? He’s not rocking out to blasphemous tunes, but listening to the diagnostic pitch that tells him if the info cannon is hitting the target.

And he’s no stranger to big name publications (such as Jalalagood) having been interviewed for the Boston Herald this April. Worth a read.