Islamic women’s attire ~ from least to most veiling…

Cross posted from: http://www.users.cloud9.net/~bradmcc/GO/attire.html

Help Fund Bold Initiative to set up Hackerspaces Across Middle East

My close friends are behind the project. Â They are talented, enthusiastic and competent. Â There is only one day left to fund this kickstarter, so please chip in and spread the word on your networks!

Would you Fund a Mercenary / Documentary Film Maker?

- Matthew VanDyke with the PKT machine gun he used in combat in Sirte, Libya

“Have you wanted to do something to help the Arab Spring but weren’t sure how? This is your chance.

In September, 2012 two famous freedom fighters from the Libyan revolution, American Matthew VanDyke and Libyan Masood Bwisir, will travel together to Syria and join the rebels on the front line against the dictator Bashar al-Assad. ”

“What is the purpose of this project and what will VanDyke and Bwisir be doing in Syria?

[Among other things, filming] Masood Bwisir entertaining and improving rebel morale with his famous revolution songs, including new ones or variations of his Libya songs modified for the Syrian revolution”

This kickstarter application reads like an audition to be picked as a character in a first person shooter. Drop a coin and hit the spacebar to select this character for the Syria level.

It feels as though the rewards should have been 25$ gets a magazine clip for AK. 100$ gets a new AK. 1$ buys chai on a hot Syrian day.

I mean, I like crazy … I just think that this kickstarter is crazy in an both old and interestingly novel ways. I spent a little bit of time trying to relate to the mind that generated this project proposal.

From here, it’s not such a distant jump to imagine crowdfunding mercenaries in third world places? Now imagine, two competing factions engaging in such fundraising, eg “campaign contributions”? I’m surprised Kickstarter has allowed this project up on the site, and I am glad that the funding has begun to stall out at the final moments.

Matthew, if you read this, why don’t you just reach out to Vice Magazine and get an advance from them to cover your expenses?

On a related note, I highly recommend you read Campaigning on the Oxus by Januarius Aloysius MacGahan.

He was an American reporter for the New York Herald Tribune who covered the Russian Army campaign in Central Asia in the late 1873 as a 29 year old. Starting from a remote Siberian town, he galloped 2,000 miles through the dessert to join the Russian forces invading Khiva. His writing is engrossing. Â On the way, he documents a visit to a Khan’s harem, and when he finally arrives, his engaged journalism takes him to the battlefield, where he participates in the slaughter of the sword fielding savages with his own rifle.

You should in the least read the opening paragraphs of the preface.

Those were the good old days!

Obitutuary for Merhab Sarahj, Taj Mahal Guesthouse Manager

According to a trusted source, we learned that the Taj Mahal guesthouse manager has been shot by two motorcycle riding gunmen.

We knew him as Mehrab, while his full name was Mehrubin Saraj. For many of us, he was more than the manager of the Taj Guest house, but our first condiut into Afghan society. He took us to purchase our Afghan clothes and explained the world outside the compoud walls.

One carefree afternoon, I asked Merhab to tell me about his life before the Taj. This is a transcription of my notes from that day:

In the 80’s we saw terrible things.

As a teenager, after a Soviet raid, I helped bury 14 members of my extended family. That night we packed all our belongings onto a donkey drawn cart. With a caravan of 23 and two cows we travelled two sleepless days to the border with Pakistan.

My father wanted to avoid the masses accumulating in refugee camps on the border, so he guided us to the hills on the outskirts of Peshawar, where he knew about some caves.

We survived as sheppards, having bartered some of our goods for animals. We sheltered inside the caves and blocked the entrance by stones each night to protect the animals from wolves and jackals. At times I would stand watch with a rifle, and tried to follow my fathers advice “aim for the bright eyes”.

My father was most concerned with the posibility that the kids would get bitten by snakes and scorpions. In time, he managed to purchase tents and we moved back to the refugee camps so that the youger kids among us could attend makeshift schools.

When the next summer came, to escape the heat, my family again went back to the higher elevations near the ancient caves, but this time we settled in the plum orchards. … and we brough others with us.

While the owners of that land had previously tolerated us as one family, they took an armed stand upon our arrival blocking our way. They worried that we would bring even more refugees with us and would start treating the land as ours.

So we went back to the caves and only went to the orchards for picnicks!

In the 90s we returned to Jalalabad. A branch of my family had escaped to Egypt and also returned. One of my brothers went missing in Iran, and I still don’t know where he is.

We recovered our home and I was married to my cousin. We lived somewhat apart in refugee camps, but my parents told me about her and made the family arrangement even before we returned.

Since then, I have tried my hand at various enterprises. I worked at what I knew best — as a shepphard for 6 months. A soap factory I started failed. I tried my hand as a beekeeper, bought 25 hives, but they all died. And then I opened a tobacco shop.

I discovered the Taj Mahal Guest house when it was run by the UN. I came on as a pool cleaner, and worked my way up to manager. First I worked closely with the Kiwis, and now with Dave.

RIP Mehrab. August 2012.

Officially for Sale

I spotted an old man sitting in a crowded bazar, sewing army and police patches onto uniforms. I haggled and picked up a dozen.

Celebrating Nowruz in Mazar-i-Sharif

We chose to celebrate the Persian New Year, Nowruz in Mazar-i-Sharif because it is the epicenter of celebration in Afghanistan. Over 200,000 people congregate at the Rowze-e-Sharif Mosque which the Afghan Shia believe houses the tomb of Hazrat Ali ibn Abi Talib whom they consider Islam’s first Imam. Nowruz is officially recognized as a national holiday and high ranking officials attend the celebrations.

Although the festivities are centered on the Mosque, Novruz is a pre-Islamic holiday that is not mentioned in the Koran. Because of this, according to some of the Sunni tradition, it is considered bid’ah (a prohibited addition to the religion.) The Shia on the other hand, consider it a celebration of Hazrat Ali’s ascent to the Caliphate on this day in 656 AD.

Both the concentration of people and the religious tensions surrounding the holiday gave us good reason to stay especially alert. The Afghan National Army (ANA) was equally concerned, essentially applying a thick security blanket to the center of Mazar, prohibiting any civilian car traffic and screening pedestrians.

Airport

Civilian Airports in Afghanistan aren’t much more than an airstrip surrounded by barbed wire. You land, walk onto the tarmac, out the chain link fence and you’re done.

At 8AM on the morning of Nowruz, we found ourselves in a desert, 8 miles outside the city, carrying a heavy load, and without transportation. Because of the military lock-down, transport vehicles were not able to reach the airport.

For at least a mile on the road leading to the airport, ANA soldiers were spaced every fifty feet. They shifted their weight from foot to foot, smoked cigarettes and stared out across a vast flat plane.

There wasn’t much for us to do other than walk, and so we did.

A convoy blazed past us towards the airport. It was comprised of fifty fancy SUVs, (Mercedes, Audi, and Toyota Landcruisers) followed by fifty police and military trucks, mostly 4x4 Toyota HiLux pickups (a favorite of the Taliban) with four seats in the truck beds for soldiers with guns. Many had machine guns mounted on the roof of the cab.

Coincidentally we landed at the same time as President Hamid Karzai and Governor Atta Muhammad Nur and these boys were here to escort them into town for a public appearance at the mosque.

After a few miles of walking, we found a taxi which we shared with a fellow pedestrian, a UNDP employee. As the city was cordoned off, the taxi dropped us on the perimeter.

Hotel Barat

Hotel bookings were at a premium for the duration of Nowruz, hard to find and with gouging prices. We relied on our friend Maiwand (the captain of Mazar’s basketball team) to secure us a room at a premium location. But in order to honor our reservation, the hotel insisted that we pay for several extra nights in advance. As this was the best option (and frankly there wasn’t another) we had to give in.

Working through a maze of security checkpoints, we eventually got to our hotel. On the way we learned that the mosque grounds were only open to women in the morning (at least until after Karzai’s appearance.)

Reception struggled to find us a room, saying that they assumed we weren’t coming since we hadn’t showed up two days ago. They had to concede all sleeping spaces to the soldiers who were everywhere, even on the roof of the hotel, and had cots there too!

We responded that we paid for the two nights before our arrival only because it was their condition for reserving the room. Eventually, they kicked out the soldiers and gave us a room on the top floor.

From our window, you could survey the entire grounds and gardens of the mosque. They constitute a sizable city park, a square perhaps a quarter mile to a side.

It was a display of primary colors. The blue tiled mosque was gleaming in the center. The gardens were festively decorated with garlands and streamers, but predominantly verdant green.

Thousands of white doves provided an areal blanket, while helicopters made surveillance laps above them, dropping confetti and toys on little red parachutes.

All the TVs were streaming live from the main courtyard of the mosque. Karzai was about to speak. We were so close that we heard the loudspeakers first and then the TV screen with a slight delay.

Given that we missed a night of sleep, Lou and I actually tried to get some rest. An hour later we were jarred awake by the sounds of artillery fire. Along with other hotel patrons, we ran up to the roof to investigate. When you hear gun fire and music in Afghanistan, you’re taught to interpret that as a wedding party. This is also the reason why many wedding parties had been bombed until the military learned to review their intelligence better.

It turned out to be a celebratory salute to Karzai.

The Funfaire at the Blue Mosque

Failing at sleep, we explored the center of Mazar, its fresh juice stands and shawarma joints. When the restriction on males was lifted, we entered the grounds of the mosque.

The atmoshpere resembled a carnival with vendors of colorful balloons and toys, blanket spreads of semiprecious rocks, jewelry, festive decorations, henna, surma, women’s panties and silk robes.

(Night also revealed thoughtfully illuminated sculptures and billboards arrayed with LEDs.)

Everyone, but especially the youth, were festooned to the Nowruz max. Girls and boys were actively participating in the gaze economy, the cautious give and take, yet not too much of either; casting furtive glances, and if caught, walking straight away.

The boys put on their shiniest shirts and fanciest brimmed hats.

I even saw some girls faces, something entirely unimaginable in Jalalabad. But even under the blue burqa clad majority you could spy the glamor of the outfits beneath and guess at the deliberation expended to compose them. Little accents on their ankles and toes communicated volumes with the small canvas that modesty afforded.

Were you a bachelor in this climate and only focused on the candidates whose face you could see, you’d be discriminating against the majority of the population. I must admit, there is a certain intrigue in not knowing what is behind the curtain. We saw a boy, tailing two glamorous girls in burqas, tempting them in a very universal way, “I have a car.â€

This gave new meaning to the term “blind dateâ€.

It all felt very foreign from the Afghanistan I came to know and rely on while living in conservative Jalalabad. While even in Jalalabad it was impossible not to read into the personal frustrations of everyone you got to know individually, it was never on public display, like this, by everyone.

They say that one of the miracles of the mosque is that when a non-white pigeon appears, it soon turns white. Though I have no proof, I think that what actually happens when a non-white one appears is that the caretaker kills it, or maybe tries to give it a whitening bath in bleach with the same result.

Jahenda Bala

In the inner courtyard, a group of Shia huddled close and were working themselves into a trance by chanting. They were present for the Jahenda Bala, a flag raising ceremony, commemorating the colors of the banner that Hazrat Ali raised in battle for Islam.

This religious practice was prohibited during the time of the Taliban and to the conditioned eye of a Sunni Pashtun, it still seemed like the work of heretics.

Even Najib revealed his prejudice. His face became flush and he said, “Let’s go. I’ll tell you about this later.â€

Afghan National Army’s most heavily armed man

We spent a couple hours waiting for Najib’s friend Sheikh in the company of the ANA’s most heavily armed man. He had a quiver with four RPGs and carried another loaded one in his hand.

Najib guided us next to him and remarked that we were in the safest place in town, but I did not agree with his assessment. There wasn’t a place for miles in overcrowded Mazar where such a weapon could be used effectively without substantial collateral damage. In fact, being next to such a war machine made me feel like more of a target.

Besides, the RPG slinger said he had only ever fired four rounds, all for practice. It’s an expensive pleasure. He claimed each round cost $10,000 but I doubt he knew what he was talking about.

There were a few kids hanging out with the soldiers. Frequently, they’d ask to play with the guns or just tugged at the barrels without asking. And soldiers, who were Afghan kids themselves and could relate, obliged, nonchalantly passing the guns around without so much as a word of caution to not point them at people.

Sheikh and Nasir

We were waiting for “Sheikhâ€. He’s a business associate of Najib’s relative Nasir. Nasir had recently run up a huge debt with Najib and then disappeared. Such a thing strains but doesn’t nullify friendships. Najib lamented, “if only we were still on good terms with Nasir, we could ride across the entire north of Afghanistan and have people slaughter goats in our honor and show us a good time. Sheikh was our stand in for Nasir and though I don’t know what it would have been like with Nasir, Sheikh was an excellent host.

Sheikh carried himself with the air of a successful businessman on the verge of securing a large construction contract with the Americans which would make him even more successful.

His first gesture was to give a crisp 100$ bill to his nephew (who doubled as his minion and driver) to get us “somethingâ€. He then flagged down a Pashtun police commander and got us an escort to the governor’s privately owned amusement park on the southern reaches of the city.

Once inside, we were surrounded by blinky lights, LEDs, glowy orbs and illuminated sculptures. It was strangely reminiscent of Burning Man. Frankly, much of this adventure felt that way. Najib got ride tokens.

Ali

In line for one of the carousel rides, we met a Russian speaking boy, Ali. He overheard me talking to Najib and came to make friends. We talked about his time in Russia, his fascination with Hip Hop. On his shoulder he carried a large boom box. He wore huge sunglasses. His skater hat was at an angle. His shoe laces were neon green and pink. We were yelling in Russian, English and Pashto, all of Sheikh, Ali, Lou, Najib and me; all screaming over each other, merry making. One of the guards approached us and tried to get Lou to leave the men’s line (where we all were and hadn’t even realized there was a separate one.) Najib and Ali started berating him loudly, eventually shooing him away. We were whipped around on tethered swings and even got pudgy Sheikh to strap in for the flight with us.

Other People’s Women

We toured the amusements and spotted a large group of girls sitting around a picnic blanket. Najib cautioned us about walking too close. He said that they are other people’s women and if we approached too close, we may have to resolve the matter with their men.

Chars

Sheikh’s driver reappeared with “chars†(the Afghan word for hash). Sheikh’s chars handling skills were masterfull, like a true charsi (chars user). We sat on train tracks in the process. Through Najib’s translation Sheikh inquired about the logistics of coming to the US and specifically how much money he’d need to save up in order to have a week’s worth of good times. “Will $20,000 be enough?†I asked his intentions. He replied defensively, “no casino, no bars, no girls… just normal things.†I said that a few thousand should be plenty. “And what if … what if, we did some casino, some bar and some girls?â€

Jama Khan

The next day Sheik showed up with a new side kick, 19 year old Jama Khan. Jama is the son of warlord Comandan Haji Akhtar دمØÙ… رتخا ÛØ¬Ø§Ø Comandan Haji Akhtar is on the Balkh Provincial Council and has a pretty awesome ride (4x4 SUV).

According to Jama and Sheikh, Jama’s oldest brother Wali Muhammad Ibrahim Khil was killed by Americans after the governor Atta Muhammad Nur told them he was working with the Taliban. Whether he was or wasn’t, it used to be that saying something like this to the Americans was a rather good way to eliminate a powerful competitor.

Sheikh was tentative with our plans. “Where you want to go? How about you come to my village?â€

Ah, that elusive Afghan village(!), idyllic, pastoral, wonderful, and … everything, except it’s infested by Taliban.  (Najib tells us that this is especially true of Sheikh’s village.)

Sheikh insisted, “I’ll make sure you are safe.â€

Najib said “Thank you, but NO†on our behalf and instead we aimed the SUV for the neighboring city of Balkh.

Picnic in Balkh

Balkh is a frail older brother to Mazar. It is an ancient city (4,000 years old) and a historical center of Zoroastrianism. Due to a Malaria outbreak in the late 19th century, the regional capital shifted to Mazar-i-Sharif (but the province is still called Balkh.)

In contrast to Mazar’s square grid around the Blue Mosque, Balk is arranged in a radial grid around a circular park containing the Green Mosque.

While his minion picked up a bag full of meat in town, Sheikh gave us a guided tour of the park. We then dropped the meat at a nearby relative’s house which we simultaneously raided for picnic supplies: a large thermos of tea, a whole service of tea cups, vinyl table cloths and woven rugs.

From there we climbed the ancient city walls of Balkh to get good views and to select the perfect (read “isolatedâ€) picnic spot. Sheikh decided on a furrowed field next to a shady grove where he unfurled the carpets in such a way that the furrows became recessed rows of seats around an elevated table.

A few more relatives appeared with the meat, already prepared, in a pot.

Hungry, we ate the lamb, the Afghans teaching us to suck out the marrow, and got our hands greasy and then handled cups of tea and Pepsi bottles, spreading the grease; and then made futile attempts to wipe our hands clean with tissue papers, which are the napkins of choice in Afghanistan.

What if “men with guns†appear?

The conversation turned to the subject of safety and how nice it is that we are sitting here with a warlords son (Jama Khan) which would be useful if men with guns appeared.

To which, Jama responded by saying that we’re safe not because of him, but because Sheikh is here.

To which Sheikh said, that if guns appear there won’t be a Sheikh here, because guns are guns and bullets don’t discriminate.

To which, everybody laughed and considered the situation resolved to the extent possible.

Kids’ Table

Not twenty feet off, behind the grove of trees, a few kids were picking at the mud and glancing at us with mischievous faces. Sheikh first shooed them away, but when they didn’t budge, he invited them to eat with us, and when they proved too shy to respond, he rounded up a bunch of meat on a plate and half of a Pepsi bottle and gave it to them. And so our picnic picked up a children’s table.

Girls can drive?

Back in Mazar, Sheikh itched to go back to the carousels. Jama Khan wanted to drive his jeep into the mountains. We compromised by driving out of the city past the carnival grounds where Jama could show us a bit of reckless driving. Then he turned to Lou and said, that if he could see a girl drive a Jeep offroad that would really make his day. And Lou took him up. In all our time in Afghanistan, we saw a female the behind the wheel just once, (and it was the Shari-Naw neighborhood of Kabul.)

Ransom for a Good Time

We initially met up with Sheikh in order to pay him back the 100$ deposit he had submitted on our behalf to Hotel Barat. And while I had given the moneys to Najib, he hadn’t completed the transfer to Sheikh. When I asked him about it, he said “Wait, I’ll give it to him at the end. This way he still has a reason to hang out with us and show us a good time!â€

Our final day in Mazar we got some shopping done, and before long Jama Khan was calling asking to hang out. He showed up with a body guard who he proudly announced was on the ministry of interior’s payroll. To prove the point he made the boy pull out his ID card and show us. Surprisingly the ID card was also his salary card. It doesn’t really matter who you are until you show up in front of the cashier at the bank. When you collect YOUR salary is when it is important to know who YOU are.

Today Jama wanted to go show us the mountains he didn’t get to the day before, and so we drove south, past the gargantuan Soviet bread factory, past the carnival grounds, past empty streets of subdivided lots with retaining walls and some construction, and then streets with lots without construction, just retaining walls, and then lots, but no retaining walls, but just gravelled roads in a grid, and outdoor sewage ditches marking their boundaries anticipating the city’s expansion. There were only shepherds there to graze their sheep, though there wasn’t much (left) to graze. The sheep tried to escape the heat by hiding in sewage ditches.

But Jama drove onward.

Juma Khan drove without regard for streets. He re-landscaped the hills.

All of these plots, I learned later, were from a planned expansion of the city orchestrated by the governor. We’ll be bigger soon! The state can make money selling plots of land!

After driving for a while we seemed no closer to the mountains in the distance. We were in the steppe and occasionally you could spot another group that voyaged to these hills.  This is where they came to escape the bustle of the city (and the Taliban of the village.) This is where they came to be alone with their families. These were the “mountains†that Jama wanted to take us to, as this is where he would come with his friends, rip donuts in his 4x4 and toke the chars.

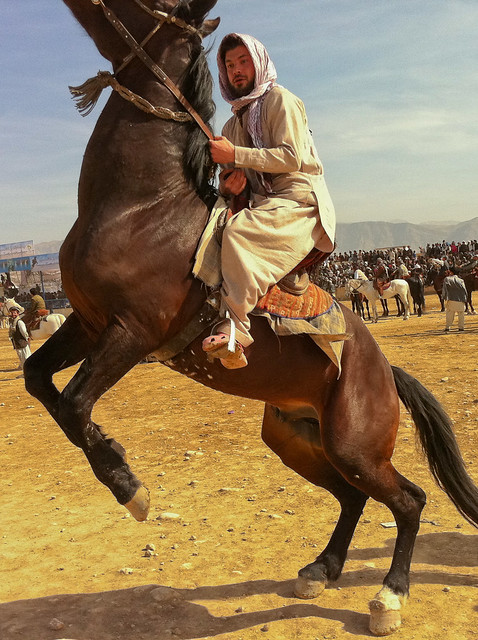

Buzkashi

(Click here for a more in-depth description of the game. )

Novruz is also the culmination of a Buzkashi season and so we asked Jama to takes us to the match. It became clear after some prodding that he didn’t feel comfortable going.

It turns out that just like American oil tycoons buy football teams, Afghan warlords maintain stables of buzkashi horses and teams of star riders under their care.

The buzkashi field therefore is not really a safe place. It’s proxy war. But real war occasionally breaks out in the stands also. It’s the one public event where personal scores are settled by assassination.

In the end, Jama agreed to take us, but “only for a little bitâ€.

These buzkashi grounds were very different from the muddy snowy pit we visited in the Panjshir Valley. It was a large hot dusty field lorded over by a gargantuan Soviet bread factory. On one side were the stands, seating several thousand people. A water truck was zig zagging through the field during the game, spraying the ground, trying to keep the dust down.

Jama disappeared and left us with his body guard. When he returned, it was on a horse. The buzkashi horses aren’t too tall, as then it would be too hard to reach down and grab the dead goat from the saddle, but they are hard workers. All of the horses were drenched in sweat yet they persisted in running full gallop at the minimal urging.

In fact, a buzkashi horse is hard to keep still. If you don’t do anything, it takes off. It’s like having a car without the gas pedal. It always assumes the pedal is floored. You have to actively say stop.

The horses are also remarkably easy to rear. Both Lou and I gave the horses a try and successfully got them on their back legs, kicking in the air, over and over again.

With Jama by our side, we were a part of the action rather than passive observers.

Our schedule was tight. From the horse track, we went to the basketball court.

Basketball Practice

My pipe dream for Mazar was that Najib and I get to join the Mazar basketball team for a practice session. I tried getting in touch with Murtazo, but for a couple days all his text messages reported that his father forbid him to go outside because it was dangerous.

Our connection was Maiwand, the captain, the same guy who helped us out with the hotel. When we met Maiwand, Najib grabbed him lovingly and they walked hand in hand all the way to the basketball court.

Neither Najib nor I were prepared to play, but they took care of us, giving us sneakers and shorts and uniforms and we went through the whole stretching, warmup and exercise routine. They split us up into teams and we played a few practice matches.

At one point, there was a loud BOOM and a pillar of smoke rose just behind the wall of the court. Some of us ducked to the groud, but then Murtazo laughed, “it’s just a truck tire blow out!†and we went back to playing.

Half way through practice, there was a tea break.

Many of the boys spoke to me in Russian on the court. They were commonly Uzbeks or Tajiks educated across the border. The coach had also studied in Russia.

Najib tried some fanciful spin move and ended up twisting his ankle. Just as he sat on the bench, Sheikh arrived. He came bearing gifts, some perfume for me and face cream for Louisa. At that point Najib asked him for Nasir’s whereabouts and gave him the 100$ bill.

Farewell Afghanistan, farewell Najib …

The next morning we were out of Mazar and the next day we were in Delhi.

Naijb was on the verge of tears when we parted. “It will be boring without you. Thank you. You’ve changed my life. I will never forget you.†I owe him at least a blog post, and probably a lot more, so that you will understand why.

I’ll just add, since it’s a feeling that I’d rather not forget, but when we boarded the Air India airplane in Kabul and I saw the female flight attendant walk by in a pair of tight fitting pants, I felt abashedly titillated. There was a sight I had been deprived for the past three and a half months. Absurd, I know, sorry.

Goodbye Jalalabad

The wind picked up on our final morning in Jalalabad. It was soon strong enough that we locked our windows and yet it howled through the cracks. By the early evening the gusts were so strong that they broke windows on the upper deck, broke our deck furniture and knocked over many plants.

We were about to leave Jalalabad, our adopted home, where I spent 1% of my life. Before heading back to San Francisco, we decided to do some in country tourism. The following day was Novruz, the Persian New Year, and we planned to spend it along with 200,000 other pilgrims in the epicenter of the celebration in Mazar-i-Sharif, the capital of the northern Afghan province Balkh which borders Uzbekistan, at the Rowze-e-Sharif Mosque housing the purported Tomb of Hazrat Ali.

Novruz is defined by the Vernal Equinox, which happens when the sun crests across the true celestial equator. Terrestrially we experiencing major shifts as well.

After Lou and I finished packing we huddled together with our coworkers to drink wine and watch the telly (for perhaps the first time.) Bombs were falling in Libiya. Egypt had experienced a coup. Other North African and Middle Eastern countries were undergoing or on the verge of revolutions.

Road to Kabul

I eagerly anticipated a certain photo opportunity on the way out of Jalalabad. Just a few miles west of our compound, near the Darunta dam, I had previously spotted (but failed to photograph) an amusing billboard with a cartoon depiction of a gaggle of bearded Afghan villagers happily handing over a Stinger missile to ISAF forces in exchange for money. No questions were asked. Everyone was smiling.

It was an advertisement for the Stinger buy back program. During the 1980s, the CIA “donated†~2,000 shoulder fired Stinger missiles to Mujaheddin “friendliesâ€. These missiles which could be used to shoot down Soviet helicopters and tanks, had a significant impact in the outcome of the war. The Pakistani intelligence agency ISI had distributed them without much accounting. Consequently, no one knows how many are still floating around. Now the US has budgeted millions to buy back stray missiles for upwards of $100k a piece. It’s cheaper than the consequences. And this creates an interesting economic valuation climate for weapons. How much is your enemy willing to pay you not to shoot at them? The “ransom priceâ€.

On the way out of town, we noticed that many of the billboards had been knocked down by the wind. Just yesterday, they were still covered with election posters six months past their due. I had wondered just when they’d be taken down and by whom. The billboards that hadn’t collapsed entirely stood warped and bare, picked clean by the sand blasts of wind.

The road to Kabul follows the course of the Kabul river, winding its way along the southern bank through hills, past three partially functioning and eternally under-repair dams, and finally up a narrow, dangerous, serpentine gorge locally known as Mohi Par (fish’s tail).

The road is dotted with makeshift shacks selling the available bounty of the land. Today men waved reams of river fish and kids shook bunches of mountain vegetables at oncoming traffic.

We passed a couple fuel tankers, a favorite target for IEDs, Their rusty tanks were leaking fuel right on the road.

Next we encountered an oncoming Afghan National Army supply convoy. Unlike ISAF convoys that drive slow and flock together, ANA seems engaged in a race with each behemoth for itself swerving around the curves.

Remarkably, right before our eyes a large container flew off the back of one of the trucks, bounced on the road, and spilled its booty of ANA uniforms onto the road.

- “Stop,†I yell to our driver Najib. I sense a really epic souvenir pickup. Gotta get this one quick. He skids to a halt, but so does the car behind us. Other people have the same idea. I run towards the uniforms and so does the grey bearded Afghan from the second car.

But before we’re able to snag the uniforms, the next truck in the convoy rounds the corner, stops in the middle of the road. Soldiers hop out with their rifles and stare us down.

“Alright, you win. You can have your uniforms.†I go back to the car with my heart pounding. Damn, it was close.

Face to Face

The motto “every car for itself†applies to every vehicle on the road. They swerve onto oncoming traffic trying to eek out ever more lanes out of two. If it wasn’t so dangerous their optimism would almost be laudable.

The one way I can explain it is that they are making a rational calculation where the variable that is drastically different from my own valuation is the value of one’s own life.

“This didn’t happen during the time of the Taliban,†said Najib. “Everyone knew their lane and what would happen if you veered outside of it.†(Of course, there were also fewer cars.)

Now what you get is a lot of avoidable gridlock. They call it glibly “face to faceâ€. It sounds nice. Sorry we were 5 hours late, “we had some face to face on the road.†And everyone understands that what is meant by this is that cars piled up for miles on a two lane road face to face without any room to maneuver. It takes a lot of coordination to clear such a mess. Eventually, somehow, with guns waiving in the air, we drove out of it.

Kabul

There was one errand left to run in Kabul. Â We needed to purchase a few point to point antennas so we headed to the computer shopping district. Â A man with a riffle walked into the store and pointed it at the shopkeeper. Â After a few seconds it became clear it was a joke. Â Ha, ha, Afghanistan.

We dropped our stuff at Una’s (the newest member of SSF but quite a veteran for an expat in Kabul) and headed out for dinner with a couple of her journalist friends.

One of the journalists, Omar Malick had just completed a documentary in Pakistan and come out to work for Basetrack.org a Knight Foundation Grantee that used Facebook to report on 1/8 Marines deployment in Kandahar. He was now straded since the military chose to terminate this experiment. Omar had instead thrown himself into iPhone hipstamatic photography and shared some amazing shots over Thai food.

Together we roved to a Novruz party at a compound of an Afghan “consulting†firm where the spread resembled that of an American college dorm party. Beers were stacked in a pyramid. Chips, salsa and munchies for appetizer. “Pizza is on the way.â€

The hosts asked us to “not be too loud and disturb the fundamentalist family that lives next door†as “they might do something about it.â€

The attendees were Afghan staff of NGOs, the UN, or various government ministries. Think of it like an Afghan beltway crowd.

The guests and employees alike were mostly educated at liberal arts colleges in the West and unanimously felt like American money was being thrown at them to try to solve the “Afghan problemâ€. Jokes around the camp fire revolved around writing impact reports and USAID proposals for firewood, which was running low.

“Afghanistan is where the money is at. For educated Afghans and for security contractors, that’s the best windfall. Where else can twenty year old boys and girls consult governments [by the seat of their pants, sometimes by just being the eyes that read on behalf of the illiterate]?â€

There was a rumor about the possibility of fireworks for Novruz so we ascended to the roof. After the countdown to midnight, nothing but the scent of Hindu Kush and gentle giggles was heard.

Airport

An early morning “Hope Taxi†gots us to the Airport. Six chambers of security, each with a male and female line, neither more secure that the last, and we’re in the main hall.

We have a Pamir Airways e‑ticket to Mazar-i-Sharif for three people. We’re happy to have Najib along. We’ve become so close and these are our last four days together. Because of the holiday the airport is crowded more than usual.

We check in at the only counter that says Mazar, even though it actually seems like a different airline. Bags are checked, paper tickets issued, no hitch.

Through another tier of security we find ourselves resting in the waiting lounge.

Out of the corner of my eye, I spot the airline employee who checked us in with a look of consternation. He’s clearly looking for somebody. He’s heading straight for us!

Evidently the Pamir fleet was grounded as part of a general Kabul Bank lending practice shake down and the airline’s inability to repay a shady $98 million loan. The airline was shut down two days before our flight. We saw Pamir planes parked at the airport. Ironically, their online ticket sales website is still running, while we are still out $900+ for our flights.

He explains to us that we had purchased tickets for an airline that ceased to exist by the time we got to the airport. He had mistakenly issued us tickets and now insists we actually pay for them to get on the flight.

Naturally we protest, but as absurd as it is, it was also clear that he was speaking the truth. No, he didn’t know how we would go about getting a refund from Pamir, but then again, neither did the many other people who were in the same situation that we were.

We paid and boarded.

To be continued …

To lose and find a child in Afghanistan …

Rawed’s father Gulzada brought him to Jalalabad city to be seen by a doctor.  Seven year old Rawed was showing symptoms of jaundice.  They drove into the city from a small village in the district of Sherzad.  As is common practice, dad temporarily left Rawed with a shopkeeper from the same village and went to park the car.  “I’ll be back in a few minutes, and then we’ll walk to the hospital.”  When he returned the child was gone.

Gulzada is our friend Haji Najib’s ma’ma’, which means maternal uncle. Â A paternal uncle is called ka’ka’.

The shopkeeper insisted, “he was just here.” When thirty minutes passed and the boy was still missing, dad called Najib.

Ma’ma: “What would you do if you lost a child in Jalalabad?”

Haji: “I’d make sure not to lose the child, and if I did …”

Ma’ma’: “I lost my son.”

Haji: “I’m on my way.”

Haji, which is how everyone calls Najib, always seems to be dealing with emergencies and he’s good at it.  We call him in like a storm trooper and he comes through. After he got this call, we lost him for two days.

So what do you do if you lose a child in Afghanistan?

Haji, Ma’ma’ and Ka’Ka’s son rented a loudspeaker, mounted it on the car, and started cruising an increasing perimeter around the site the boy was last seen.  They brought Ka’ka’s son along because he has a memorable cellphone number.  They figured this was important if you were going to be shouting it out in passing.

“Dear fellow Muslims, we have lost a 7 year old child around 9am. Â He was wearing grey clothing and white shoes. Â If you have any information, please call 077 77 20 900.”

They kept repeating this fruitlessly until 3pm.  And then a 15 year old boy who sells phone cards in a road side shack ran up to the car.

“I’ve seen your son.  He was with me until 11:30am.  He was crying and I tried to calm him.  I bought him an orange.  He refused.  I bought an apple.  He refused.  He kept saying my home is there and pointed at the horison.  ‘I want to go back home to Sherzad.’ ”

The 15 year old found a 10 year old who was from the same district.  As it later turned out, that was a fortuitous move.  The 10 year old was a relative.  But neither the 10 year old or Rawed knew their relation.

The 10 year old was instructed to bring Rawed home.  Surely, someone from Sherzad should take care of a missing child from Sherzad. Unfortunately, Rawed did not cooperate.  He kept crying and just minutes later refused to go any further.  “I want my dad.”

As it happens in fairy tales, three tweleve year old boys chanced upon Rawed and his 10 year old companion.  They inquired, deliberated, and decided that they should take Rawed.

They did the sensible thing.  They first took him to the nearest Mosque and having announced the case and consulted with the Mullah, they decided to start scanning their own perimiter, on foot, announcing:

“Dear Muslims, we have a lost child. Â Here he is. Â Look at him. He is from the village of Shirzad. Â Help us find his parents.”

And they walked like this for many hours.  Even Haji Najib heard about them from people who walked up to his car with the loudspeaker.  The twelve year old boys tried diligently.  After many hours, when the

sun was near to setting, at 5pm, they met a 25 year old man in a car. Â He was also from the same village and offered to help the boys out. Â He would take Rawed and help him find his father.

By this point, the loudspeaker broke twice and Haji Najib and crew had both times replaced it.  They also requested an announcement to be broadcast on three radio stations at 11 am.   They wore our their voices, taking turns, until 10pm.

At this point, activity stopped on the street, and Haji, Rawed’s dad, and all of the male members of the family present in Jalalabad gathered around the dinner table and made their plans for the following day.

They decided to break up into teams.  At this point, they heard about the 12 year old boys and the fact that they connected with a local Mosque.  They figured, one team will canvas the schools and one the Mosques.  Surely, they would find him.  A third team, lead by Haji, would contine enlaging the perimeter with the loudspeaker.  If neither party found the boy by 4pm, they would make an announcement on television.

After a sleepless night, they set out at 6am.  They had no success.  Haji started to get phone calls from a man claiming to have found the child.

“Consider as if he is with his mother and father.  If you pay money, you have nothing to worry about.”

The phone calls persisted.  The sums requested were small, maybe 10$ worth of phone credit, but the caller refused to allow contact with the child.

It is not uncommon (in Afghanistan as elsewhere) for people to opportunistically prey on other people’s vulnerabilities. Haji’s phone number had been announced on the radio, so the caller could just be a prank. Nevertheless, it was the one active lead, so Haji started taping his conversations, dragging them out and trying to extract as much information as possible.

At 4:30pm they delivered a photo from Gulzada’s phone camera to a local television station, RTA (Radio Television Afghanistan).  Then they resumed driving around with the loudspeaker.

Hameed joined the crew at 5pm and took over the announcements with a fresh voice.  At 7pm of the second day, the loudspeaker broke for the third and final time.  It was too late for repairs or a replacement.  And they were worn out.

They returned home for sustainance and an all hands meeting.  After dinner and tea, the search party, which by then had grown to 10 people, crashed out in Haji’s family’s living room.

At 9pm, the elder of the house (a law professor at Ariana University who had studied in Bulgaria) roused them with news that Rawed’s face had just been shown on RTA television.  And at 9:45pm Haji got a call from another number, saying that they had the kid.

It turns out, that the 25 year old brought Rawed home as promised. His father, a big merchent in town, handed the boy to one of his employees for care.  This way Rawed spent the second day in the village of Baze ik Malati (where Baze refers to its proximity to the American base at JAF, Jalalabad Airforce Base).

On the phone they agreed to meet at a public square called Chowk Muhbrat.  The merchant and his 25 year old son came alone. When they confirmed the identity of the child with a photo, they agreed to exchange Rawed at the police station.

The merchant drove with Haji, while his 25 year old son went to fetch Rawed.

At the station, Haji ran up to hug Rawed, but Rawed looked startled as if he hadn’t recognized his cousin, and started to cry for his father. I’m not sure why they didn’t bring his father in the first place, but at this point, they sent a car for him.

In his fathers arms, Rawed cried and laughed.  The identification was complete and the celebration started. One of Haji’s uncles gave 2000 Afs to the merchant as a finder’s fee and another 500 to his 25 year old son. Another uncle gave 2000 Pakistani Rupees to the 25 year old.  The police asked for some too, saying they also wanted to celebrate.  So they gave 500 Rupees to one officer and another 500 to the clerk who filled out the paperwork.

They also picked up oranges and apples and handed them out to everyone. The following day Rawed and Gulzada went back to their village carrying a load of fruits, tea and sugar from the big city, expecting to host lots of relatives in the village who were aware of the situation and understandably concerned. They did not stop to visit the doctor in Jalalabad.  Another one of Haji’s uncles is a Tajikistan educated doctor that lives in Sherzad and runs a pharmacy, so they decided to bring the boy to him.

In the final tally, Rawed had changed hands from his father, the shopkeeper, the 15 year old, the tweleve year olds, checked in at a local Mosque, the 25 year old, his merchant father, spent the night at the merchant’s employee’s house and was finally reunited with family at the police station.

The search party (which grew to ten people and involved many others) lasted for two days and spent a few hundred dollars on loudspeaker rental, repairs and replacements, gas, photo reproductions, food and fruits.

In the end, they found Rawed.

Najib called the original caller back another time.  He asked whether he still had the child.  The guy claimed he had.  How did you get him?  Najib asked.  “An Army commander gave him to me.”  Najib cursed him out.  Either this was all a ploy, or another child is still out there, kidnapped.

Buzkashi

On a down day in Kabul, we decided to take a road trip up to Panjshir Valley. Lou has written about our experiences in a previous post. This post focuses on the game of Buzkashi.

The objective of Buzkashi is to gain possession of a goat carcass, carry it a full loop around the field, and then deposit it into your opponents goal (which is a circle on the ground). If at any time you drop the goat, you have to restart the loop again.  There are referees who determine whether the goat has been deposited in the goal correctly. Here’s a frame of the players looking for the call from the ref.

Losing possession means you either dropped the goat or someone yanked it out of you, like a fumble in American football. Here you see the dead goat on the ground among the pile of horses. Now one of the players has to lean down off his horse (without dismounting and pick up the ~100lb carcass).  That is a dangerous proposition. Hopefully your friends have blocked out your opponents well, before you try. Otherwise you will get trampled.

Mark the Soviet Tanker helmets many of the players are wearing in this

I asked them where they got the helmets. They said it was form the Soviet Tankers they killed. Up and down the valley, there are hundreds of scattered tanks. Four helmets per tank. I believe them. Nowadays, some wear American Army gear.

The rider in the center is trying to reach down and grab the goat.

Mud soaked from falling.

This rider got up and rode again. It is a brutal sport. You show your mettle to your fellow villagers.

Sometimes it takes four hands to brag the goat.

Here you can see a formation. The three on the right are like the linebackers. Then one behind them is ready to block out another team. And the two behind him are sharing the load of carrying the goat.

Taking photos from the crowd. And now turning the camera at the crowd.

On the way back home, our car shared the road with Buzkashi riders on horses. This one tried to grab my camera. Instead, I got a shot and then reached out and shook his hand.

Now see it all in action (thanks Lou!):

How the Taliban hijacked our educational materials…

Our Malik Dave had a wonderful idea. The reasoning went something like this:

Let’s employ the Afghan companies that sprung up to print election posters.

They are currently out of work because the election season is over.

Lest we hire them, they may be up to no good.

We call this technique weaponized shopping and it’s one of the techniques in the arsenal of the Synergy Strike Force.

Over the past month, Lou, Juan and crew have put themselves towards selecting and optimizing high quality image files for large format printing of educational materials. We did a test run with the printers and then submitted our final order. Yesterday, (Sunday 20th) Hameed and Najib went to pick up the posters.

As things turn out here, the shop owner had been arrested by the police on suspicion of printing materials for (Al Qaeda or) the Taliban. When the police raided the store, they sensibly confiscated all of the printed materials in their possession as evidence. Among this pile currently in procession of the police are posters on the subjects of cell biology, hydrology, and the periodic table of elements.

Hopefully, we’ll get them back. We did pay a good 4,000 Pakistani Rupee equivalent of 45$ Pakistani Rupees, called “Caldari” are the de facto currency of Jalalabad deposit.

Such a day’s course of events is starting to seem perversely normal for us, as much as I can still imagine seems perversely abnormal for those whom I usually count as peers.

***

Two days ago (Saturday Saturday is the first day of the work week. 19th) an attack took place in the center of town focused on Kabul bank where police officers were collecting their pay. From our sources at the hospital upwards of 40 people have died and many others are in critical condition. Among the dead are reported the “deputy police chief and the head of criminal investigation.”

Many of our friends at the public hospital were on high alert dealing with the patients that stretched their capacity. Meanwhile our friends at a local radio station were broadcasting the need for blood donors across the airways, resulting in hundreds of donors showing up at the hospital, ready to give.

Our friends say that the only day in recent memory that compares at the level of impact was when protests erupted in 2005 after it was alleged that the Koran had been flushed down the toilet in Guantanamo. Â The differences are stark. There are many more civilian casualties and this was not a popular uprising.

***

Yesterday (Sunday 20th) was a day of mourning. Two of our guards had lost a brother. Many of our friends had checked out for the day to attend funerals for friends, relatives and acquaintances. Our UPS (uninterrupted power supply system) had died but we couldn’t get it repaired because the shop of the company that had built it was also damaged in the explosion.

***

We got hold of some exclusive footage.

In this video you see a captured insurgent and security video showing how he entered the bank dressed as a police officer and started firing. Several things stand out. Firstly, he looks like a clean cut young man, nothing like what we have learned to think of as insurgent or terrorist. Second, while he is firing hordes of people run past him, within a foot in distance, and none of them give his vulnerable backside a good whack.