Entering the FOB

If you search for Jalalabad on googlemaps only one road shows up, Hwy A01, the Asian Highway, a.k.a. Kabul-Jalalabad-Torkham Highway. Â That road is the main drag of Jalalabad City, sporting twoish lanes of traffic flowing each direction, packed with tuktuks, motorbikes, donkeys, tracktors and toyota corollas, all jamming for space.

The main US army base in our region is FOB Fenty, located on the eastern edge of Jalalabad City. It’s a well-established base that’s been around for many years.  It’s main gate directly opens onto the Highway.  Part of the security protocol for handling entrances and exits to the base requires clearing the road in both directions for about 100 feet to prevent any opportunistic assaults. This tends to make for interesting traffic jams:

The main gate to the base is a 20 foot wide steel door with a large guard post on one side. Parked behind the steel door is an MRAP to further block the door should any one attempt to smash through it.

If any vehicle, including MRAPs, ANA pick up trucks, supply convoys, or personal cars pull up to the gate to enter the base, protocol requires that the area around the gate must be secure before it can be opened. This entails a dozen fully armed soldiers dispersing into the road and stopping traffic 100 feet back from the gate going both directions. Only once all the traffic on the main road in Jalalabad has been ground to a halt, can the security MRAP be backed up to allow the gate to open, and the vehicle to enter. Once the vehicle is safety in, the gate is closed, Â the MRAP has been driven back into place, then traffic can start flowing again.

Imagine if a highway you drove between home and work was intermittently blocked in both directions by guys cursing at you in a foreign language, “stop,  stay the fuck back” while pointing rifles in your face and occasionally firing warning shots.

How is this set up supposed to win the “hearts and minds†of the Afghan people?

The security procedures make sense as the base is often a target of attacks, but after years of this mayhem maybe the army should think about moving this heavily trafficked, highly secure entryway onto a side street, perhaps off the major highway running through town.

Etymological Weaponry

Two representative symbols of Afghanistan, grenades and pomegranates, come from the same etymological root. We discovered yesterday that the word “grenade” is taken from the French “pome-grenate.” French soldiers gave the handheld explosives their name because they looked like the seeded fruits, both in their round shape topped with a crown, and in their inner workings consisting of lots of small seeds, prepped for activation.  We keep a stock of both at the Taj.

Meanwhile, “RPG” is usually miss-translated as “rocket propelled grenade.” Its a memorable term that fits the letters and sounds like it could be right, but isn’t. Here the Soviets can claim origin as the letters actually originate from ручной противотанковый гранатомёт, meaning “hand-held, anti-tank, grenade launcher.” It’s not quite as catchy in English because “HHATGL” doesn’t have the same ring as “RPG”, so we’ve adopted the acronym while making up a handy substitute for the letters. Plus, “rocket propelled” sounds bad ass.

Of Lions and Horses in the Panshir

Last Friday morning we headed off at first light from the muddy streets of Kabul. We wound our way north, past Bagram, where ISAF is headquartered, and took a sharp turn east in the village of Jebal Seraj. We’d decided to take a day long pilgrimage, of sorts, to the tomb of Ahmad Shah Masoud. His grave lies deep his homeland of the Panshir Valley which he so famously defended against the long and arduous Soviet attack.

Masoud is arguably Afghanistan’s biggest hero. Throughout Afghanistan his picture is displayed in car windows, posted on buildings, or memorialized in woven blankets. The day he was assassinated, September 9, 2001, by suspected Al Qaeda agents posing as journalists, is a national holiday. He earned his title “The Lion of the Panshir” defending his home turf from the Soviets during the attacks of the 1980s. Lions are intrinsically part of Panshir culture. The word itself means “Five Lions†and we saw election posters for a candidate whose symbol was four of the majestic beasts. (Each candidate is “randomly assigned†a visual symbol so illiterate people can recognize their candidate on the ballot. It’s well known that with the right funds and connections it is possible to influence on this “random assignment.†One political party paid for all of its candidates in different races to have apples for icons, to present uniformity to its illiterate supporters.)

During the Soviet invasion of the 1980’s the Lion of the Panshir and his mujahideen fighters would descend from the valley, attack the Soviet supply chains heading across the Salang pass to Kabul, and retreat with their stolen booty. The Soviets tried to dislodge him from the valley in ten separate offensive attacks. All of them failed.

When the communists fell from power Masoud served in the mujahideen government as Minister of Defense for the few years before the Taliban took power. He then retreated back to his valley, from where he continued fighting the Taliban, (until the bomb hidden in the disguised journalists’ camera made him a martyr.) When he died he was the leader of the Northern Alliance, or the United Islamic Front-an unprecedented multi-ethnic group of leaders who fought against the Taliban government and, once the US began carpet bombing post September 11, took control of Afghanistan.

In 2002 Mosoud was post humously nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. (However, the prize can only be awarded to a living person.) He was buried 30 km from the entrance to the valley, near the village that was his home. Originally it was a plain, simple grave on a large promenade overlooking the valley, but recently a massive marble structure has been erected over the grave, with plans already in construction to add a large mosque and building complex to the site.

This was our initial destination as we made our way up the valley, driving alongside the Panshir river, stopping to climb around in the rusted shells of discarded tanks and helicopters, until we reached the hillside crested with the marble monolith. We paid our respects to the great hero, along side with a steady stream of others, local and visitors, who often stopped to pray at the holy grave site.

The path approaching the site was lined with a variety of Soviet armored vehicles, some spray painted with the Taliban’s symbol (were they captured as Panshiri loot during a battle 15 years ago?). A few bees had taken up residence behind the screen of one of the instrument panels, creating a cluster of perfectly geometrical cells, whose inhabitants and makers were now frozen to death by the chilly winter. Beyond the high promenade, fields spread out across the valley, sewn with snow.

As we climbed around the rusty metal, the wind whipped falling snow at us priming us for some hot tea, so we went in search of a chaihana. As we drove up the valley we stopped to ask men wrapped in green Uzbek robes, huddled against the cold, where we might be able to get some chai and a bite to eat. “Fifteen minutes up the road†seemed to be the standard response. After a few incarnations of this, the road finally passed through a tiny town center, complete with a mosque, a few stores, and exactly one place to get food.

We stomped in and huddled near the fire they lit for us. After realizing all they had was beef broth and tea, so Najib took charge and sent the employees to the bazar for supplies and then ended up cooking up the meal himself. I’ve encountered few restaurants where you bring your own food and cook for yourself.

Grateful to be out of the car and out of the cold, we relaxed on the raised wooden platform covered in carpets. The other patron across the way started chatting with us. We learned from him that every Friday in winter the village played Buzkashi on a field just down the street. They were now on a break for prayer, but would resume the game in an hour. He invited us to come watch.

Buzkashi is the national sport of Afghanistan. It’s a winter sport, played on horses, somewhat like polo. Two teams compete to grab a dead goat and transport it across a field into one of two goal circles. Usually two villages compete against one another and there are cash prizes for the players who score goals.

The match we saw was played in a large field of mud and snow. A clump of players reared their mounts, smashing and pushing one another in attempts to reach down and scoop the 36 kilo dead goat off the ground. Many of the players wore Soviet tanker hats. When asked how they acquired their headgear they answered “We took them from the Russians we killed.” Four hats per tank, hundreds of tanks, you do the math. As they kicked and whipped and pushed, the horses’ and players’ legs alike were covered in muddy brown slush and the goat was indecipherable from a bag of mud.

And so we spent the afternoon huddled against the cold with the entire population of a small Panshir Village, watching horses and men fight each other to carry a dead goat across the valley.

Epilogue: On our journey home we stopped to watch some kids shoot snowballs across a field using a long slingshot apparatus. When they realized I was videotaping they quickly pushed their ace slingshotter forward, encouraging him to display his talent. They then taught Peretz how to shoot, applauding his efforts. His number two shot earned him much whasta.

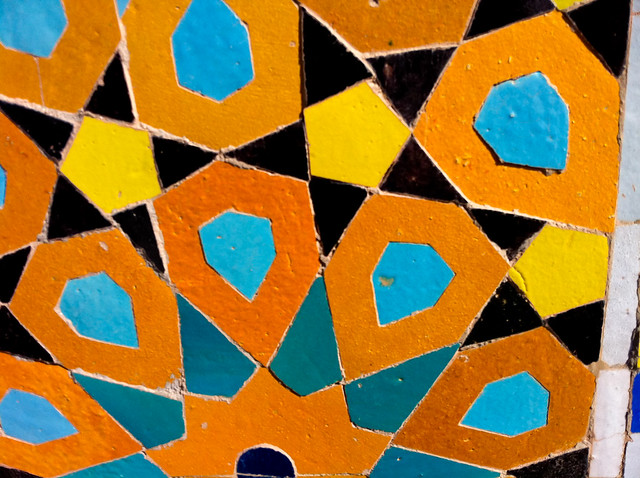

Tile Porn

Presented here for your visual entertainment and aesthetic enlightenment are images from Herat’s Friday Mosque, one of the gems of Islamic Architecture.

Traffic fLaws

Ostensibly, in Afghanistan, traffic drives on the right hand side of the road. However, this rule is leniently applied. In Afghanistan the road is used for driving, and if the left hand side of the road is open, a driver will take it.  Today while cruising down the lane of opposing traffic, we had to edge back into the regular flow to pass a checkpoint. The guard was angry.

“Why were driving on the other side of the street??†He demanded, according to Najib’s translation.

“What did you tell him?†I asked.

“That I had foreign guests in the car! [Referring to us]†Was the answer.

I saw one driver in Kabul even drive up onto the sidewalk. No small commitment because the street is separated from it by a 2 foot deep ditch so he’d have to drive the length of the city block before getting back. Still, the road was full of cars honking but the sidewalk only had pedestrians on it- and they learn quickly to get out of the way.

With all this chaos you’d think that there would be lots of accidents. And you’d be very right. The road from Kabul to Jalalabad winds down gorges for miles before opening up into the plains of Nangarhar. This is where 16,000 British Troops and their families were notoriously slaughtered in their retreat from Kabul in 1842. One lone survivor, Dr. Brydon, made it out of the valley to Jalalabad. As the story goes, the Afghans let him survive so someone could tell the tale. Meanwhile, today the gorge is not dangerous because of IEDs or Afghans shooting from the hills but because of horrible driving. Dr. Baz Mohammad, the director of the Public Hospital told me that in this year already there have been 1400 accidents and 300 deaths on that road. He knows because many of the patients treated at his hospital are victims of those crashes. (The Afghan calendar starts on the Vernal Equinox, and so these figures cover 9 months of accidents, not just 1.)

The main road in the city of Jalalabad has a divider down the middle of it, in a futile attempt to keep traffic on its own side of the road. Often it works, but it’s certainly not uncommon to see a vehicle driving the wrong way on your side of the barrier. They’re committing to driving against traffic, acting on the assumption that traffic flowing against them will all spot them in time to swerve around their oncoming car.

There are no road signs in Jalalabad. Drivers indicate they are passing by honking loudly. No on uses left or right blinkers as turn signals, but it is locally understood that flashing your blinkers means you plan on hurtling straight through an intersection, regardless of oncoming traffic. The only streetlights in the city are found at one particularly busy traffic circle in the middle of town. They aren’t powered. Instead, a cop with a shrill whistle and a stop sign the size of small diner plate stands in front of the lights, waving his sign menacingly while being thoroughly ignored by the cars fighting to get by. Roundabouts are common here, and drivers usually go the same way around them. Not always.

Taking a turn, especially a left-hand one, is not for the overly carious. Cars will not let you turn unless you give them no other option. The only way you’ll be let into the flow of traffic on a busy street is if you get the hood of your corolla nosed in far enough that cars can’t swerve around it. The rule of the road is that you never give up space to anyone if you can’t help it. This includes budging an inch for the army truck with 4 men holding AKs in the back trying to wedge its way into traffic. No exceptions given. When we riding in the Teaching Hospital’s Ambulance (they sent it to the Taj for our ride) its driver turned on the siren in a vain attempt to push faster through traffic. The siren had little effect. It could barely be heard above the honking of horns, not that people would have heeded it if it had been louder.

Parking is also haphazard. There aren’t really parking spots downtown so much as there are gaps between food carts where you can stash your car for a while. The cops, Mehrab told me, don’t give tickets because “no one would pay them.†Instead, they go around with a screwdriver and take the license plate of cars parked “illegally.†(The vast majority of parked cars here would qualify as this in America.) That way, drivers have to go to the police station and pay to get their license plate back. The fee is nominal, but the hassle of having to pick it up is supposed to deter.

Most cars are bought on auction in America (after having been totaled) imported and repaired. You often see plates from CA, MA, TX, and even from Canada.

The oddest accident I’ve almost gotten into involved a van diving in front of us whose wheel popped completely off the vehicle. Maybe the nuts weren’t tightened, otherwise they were rusted completely through because the whole tire with its wheel popped off the axle and flew across the road, into oncoming traffic, smashed into the front of a car going the other way, and ricocheted back into our lane. Najib slammed on the brakes as the tire bounced across the road in front of us. Meanwhile the driver of the van had managed to keep control and pull it over to the side, undamaged if you don’t count the missing tire.  The car that took the brunt of the tire seemed to have a smashed front light, but little other damaged. And we cruised between the two stopped vehicles, heading into town.

Guns and Welding

I was playing around with my stick welding skills when I attracted the interest of one of our security guards. He wandered up, trying to look nonchalant, to check out what I was doing that was making so many sparks. I showed him the section of an ammo case lid where I had ground off the paint and was practicing laying welds.

When he saw I also had a 40mm bullet casing, then he got really excited. He pulled out a clip of live ammunition from his cammo vest and took an AK round out to ask, through gestures and hand signals if what I had was also a bullet. I nodded in agreement and he was hooked. Unfortunately, the bullet casing turned out to be aluminum not steel, but I had acquired my first student.

Meanwhile, during our bullet exchange, Mustafa, the “house commander†joined us. Not wanting to be left out of the fun he picked up my angle grinder and gestured how he should use it, looking to me for a nod of assent. I showed him where the button was and next thing I knew the two guards were grinding all the paint off of my ammo case, prepping it beautifully for lots of welding practice. If we got those two guards into the Boxshop, all our FLG grinding problems would be over. They worked the thing meticulously, getting at every scrap of green paint until the thing shone.

And that’s how I came to teach two Afghan men with very large guns who speak absolutely no English how to stick weld. We’ve arranged for lesson two tomorrow, inshallah, as they say here.

Ladies Night…. Or Afternoon

The park in Jalalabad is, like so many other public venues, open to men only. However, Wednesday is special. Wednesday is Ladies Day.

So Jenn, Kellie and I decided to take a soccer ball and spend a few hours hanging out in the park with the Ladies of Jalalabad. The park is surround by tall walls, shielding it from the views of passersby and the entrance is guarded, per usual, by a young man in fatigues holding an AK-47. He gave us a nod of approval and we slipped through the gate to the other side.

Women on the streets of Jalalabad move quickly and purposefully from one destination from the next, covered in sky blue burqas. They don’t linger on the streets with the men. If lucky you may catch glimpses of red or purple pants or a sparkly dress under the burqa’s cloak, but women are largely anonymous, covered creatures in public.

However, the park on Ladies day, safe from the eyes of men, is an outlet. An opportunity for girls and women to enjoy being outside, uncovered, largely free. They sat in clusters and groups, burqas cast aside, dressed in bright colors with heavy layers of kohl and lipstick painted on. I have no way of knowing if they always are so done up or if the park was an excuse to really dress up, but the golden fields of parched grass were covered in the saturated greens, pinks, reds and purples of the tunics and headscarves of these women.

While their mothers and older sisters sat in the grass, picnicking and drinking tea, hordes of children ran around, screaming, playing, and fighting with one another. When Kellie, Jenn and I starting kicking a soccer ball around and invited some kids to join us we nearly started a riot as the cluster of kids raced after the ball.

The kids also love having their photos taken. The boys especially will preen and strut in front of my lens, trying on different poses and hamming it up. The girls bring forward their baby brothers for photo ops, their way of trying to get captured on film. They’ve been taught they shouldn’t have their photo taken, but if it happens that they are holding a baby who is being photographed and they make it into the shot…..

As we were obviously not Afghans, we garnered lots of attention, not only for our soccer ball and cameras. Young women frequently approached us, chattering away in Pashto, not caring that we had no clue what they were saying. They showed us their babies, offered us tea, and gestured emphatically to get points across that were thoroughly opaque to us. Smiles abounded and we nodded enthusiastically, not knowing what we were agreeing with.

A few men are allowed in the park- they run the food stalls and the photography studio in one corner. For some reason this arrangement is understood as acceptable and the girls pose for photographs and buy ice cream cones with their headscarves down.

However, the guard on duty within the walls was female as well- the first female Afghan security personal I’ve seen. She was a stocky woman in fatigues and black headscarf who brandished her large knife menacingly at kids who appeared to be misbehaving. Unlike every male in fatigues, she had no gun.

After a few hours of enjoying the sunshine we said our goodbyes to new friends, promised to return next week, covered up our hair once more, and passed back onto the street, back into the realm of men.

Hardware Shopping

As it turns out, Jalalabad has no Home Depot. Not even an ACE Hardware. So, when I wanted to purchase an arc welder  to make furniture and art out of old ammo cases and bullet casings, Mehrab took me and Peretz to the bazaar. More specifically, to the hardware store section. Jam packed stalls nestled next to one another, crammed and overflowing with jumper cables, machine belts, rusty bolts, and cheap Chinese screw drivers. Functioning as individual isles of the larger bazaar,  the coexisting shops all stock many tools while each specializing in a few. A customer starts a relationship with one owner, who then sends runners from their staff to other shops along the way to grab any items not in stock. We choose a shop, out of accident more than reason, and began the process of buying tools.

First, we collected assorted wrenches, hammers, and screwdrivers, gesturing “bigger,†“smaller†or “heavier†to suit our needs. We perused the single aisle, avoiding the pair of chickens roosting under the fully stacked shelves. Angle grinder. Leather gloves. Welding goggles. Check. Our shopkeeper showed us a file and told us it was “Good quality. Made in India.†Even Afghans have disregard for cheap Chinese made tools, although the store was still full of them. The quality products they see come from India, hopping over Pakistan to compete with inferior goods.

Then onto the reason we were there: a welder. The shop sold one option, a red metal box with 5 thick screws protruding, announcing the amps they would draw, and a grounding screw sticking out the side. Instead of a power cord, two bare wires extended, ready to be stuck directly into a socket, as is the local preferred method of “plugging in†an appliance. However, for this compact metal box to be useful as a welder we needed to piece together its attachments. The store sold us eight meters of heavy duty wire, cut off a large yellow spool. Next, we debated the merits of the two options for handles and settled on a heavy duty grip. But when I inquired about a grounding clamp, vitally needed to complete a welding arc, our shopkeeper seemed perplexed. He sent one of the boys lingering in the shop off to find one, while he encouraged us to drink some chai. We perched on tanks of gas and sipped steaming hot cups of sweetened, cardamom flavored tea until the boy returned, with a pair of jumper cable clips. Not exactly what I had in mind, but it’d do.

The bits and bobs added up to most of what would be needed or useful for arc welding and so, as we paid the shopkeeper, our tools and supplies were loaded into a wheelbarrow for transport. Next step: assembly and testing of the MacGyver welder.

Disaster Services

Yesterday Megan and I taught CPR to a group of University Students who have taken it upon themselves to form a Disaster Response team and are trying to amass skills and knowledge that will be of use to them and their communities. One of the boys, Hameed, is part of our informal “geek squad†at the Taj and wrote the previous post on this blog. Of the four he was the only one who spoke fully fluent English. Two could get by in English and the fourth spoke none, although he was fluent in Pashto, Dari, Urdu and Russian. Many Afghans in this area can speak and read (if they are literate)  Pashto, Dari and Urdu. If they are in their forties or fifties, they can get by in Russian. The younger generation tends to know dabbling of English. Pashto is the main spoken language but Dari seeps in from the West, Urdu from the East, and Western Languages trickle in through the occupying armies stationed here.

The class was punctuated by Hameed’s rapid fire translation, side conversations in Pashto, and the boys wrestling matches as they were a little overenthusiastic when practicing the Heimlich maneuver on one another. The best part of the class was the myriad of questions the boys had, indicating both a sincere desire to learn skills applicable to disasters they had witnessed first hand, as well as exposing deep seated cultural difficulties that never arose in my numerous First Aid re-certification classes.

Noorahmad probed about how to clear water from a person’s lungs, the memories of last year’s flooding and earthquake still penetrating.

They asked about the spread of infection and how they were supposed to avoid getting diseases when sweeping a victim’s mouth clean or providing rescue breathing. (The next step of preparation involves each of them assembling a medkit, complete with lots of latex gloves).

Through Hameed’s translation, Najib explained to me that he was from a very rural area where there were no trained medical personal in any kind of proximity. He wanted advice for pregnant women that he could bring back to the village and disperse. According to the UN, Afghanistan has the second highest infant mortality rate in the world, topped only by Seirra Leone. It is the only non-African country in the top twenty-five. Access to information on pregnancy and birthing, let alone trained medical workers, is slim at best. Even where there are medical facilities, misinformation abounds. I was shocked to find out last night that the director of the Neonatal ward at the Public Hospital in Jalalabad has never seen a live birth.

Rahmat raised his hand and said “In our culture we are not supposed to touch women. What should we do if it is a woman who is not breathing?â€Although surprising to my western sensibilities, the question is of utmost importance. Most women in Jalalabad still wear their burqas in public. Although Afghan society is extremely physical, it is so in a fully segregated way. Men and boys are always play wrestling, hugging, and walking with their arms around each other, but the two sexes never touch in public.  Meanwhile, in the privacy of the university’s two-month-old women’s dorm, I chatted with half a dozen teenage college girls play wrestling in their own way- hugging, poking and slapping. Still, one girl there was married and five months pregnant yet her husband lived across campus in a men’s dorm. There was no place they could live together within the orbit of the school.

Even in a life or death situation, where a women would die if she were not given a few breaths of oxygen, there is a hesitation if it is the right thing to do. The question was not uncaring, quite the opposite, but it reflected the extreme chasm between men and women which will take more than an effective counter-insurgency force and an army of predator drones to solve. In the end, if these boys ever have to perform life saving aid they will have to make those decisions for themselves.

Nan Factory

While walking down the streets of Kabul last week I stared a little too inquisitively into a nan store/factory pumping out the long, flat bread that is eaten with every meal in Afghanistan. The man stretching the dough noticed my prying and invited us in to see the whole process up close, encouraging us to take photographs and film the intricate, six man team working together to form the vat of dough into identical diamonds of flat bread. The bread is baked in a clay tandoori oven, stuck vertically up against the inside wall. As the finished bread is pulled off the oven walls with long iron hooks, a man in the window sells the hot, steaming finished product to customers, who frequently go away with half a dozen or more loaves. In a traditional Afghan meal instead of a plate each person is given a full loaf of bread. He or she tears off chunks and uses them in place of utensils to scoop up chunks of lamb or beans. They sent us away with a steaming, flat, piece of nan. Delicious.